[Apologies for the long delay on this one, a combination of writer’s block and a house move slowed me down this summer. Hopefully the next installment will follow more rapidly!]

Railroads and Continental Power

The Victorian Era saw the age of steam at its flood tide. Steam-powered ships could decide the fate of world affairs, a fact that shaped empires around the demands of steam, and that made Britain the peerless powerof the age. But steam created or extended commercial and cultural networks as well as military and political ones. Faster communication and transportation allowed imperial centers to more easily project power, but it also allowed goods and ideas to flow more easily along the same links. Arguably, it was more often commercial than imperial interests that drove the building of steamships, the sinking of cables and the laying of rail, although in many cases the two interests were so entangled that they can hardly be separated: the primary attraction of an empire, after all (other than prestige) lay in the material advantages to be extracted from the conquered territories.

The growth of the rail system in the United States provides a case study in this entanglement. While British commercial and imperial power derived from its command of the oceans, America drew strength from the continental scale of its dominions. Steamboats had gone some way to making the vast interior more accessible, and played a supporting role in the wars that wrested control of the continent from the Native American nations and Mexico. A steam-powered fleet raided Mexican ports and helped seize a coastal base for the Army at Vera Cruz in 1847, but the Army then had to march hundreds of miles overland to capture Mexico City, supplied by pack mules. Likewise, steamboats delivered troops and supplied firepower in the numerous Indian Wars of the nineteenth century, when a nearby navigable waterway existed.[1] But more often than not, the Army relied on literal horsepower.

The technology that did bind the continent once and for all by steam power was the railroad. The early development of rails in the U.S. recapitulated the British story, on a smaller scale and in a compressed timeframe: horse-drawn mine rails led to small local horse-drawn freight networks, which were followed in turn by intercity lines carrying a mix of passengers and freight, which then finally, gradually adopted steam locomotives as their exclusive source of rail traction.

All the pieces were thus in place for a rail boom in the U.S. in the 1830s, roughly contemporaneous with the explosion of railways in Britain.[2] The American merchant class threw their money at rail projects, drawn to the new technology by avarice and driven towards it by fear. The Erie Canal was the chief symbol and author of that fear. Completed in 1825, it threatened to drain all the wealth of the West into New York City via the Great Lakes. Other leading mercantile cities on the seaboard—such as Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Charleston—risked being bypassed and left behind without a gateway to the growing population and commerce of the west. Their states reacted with grand projects to compete with New York’s.[3]

Cutting a canal of their own was one option, of course, but without an existing watercourse going in the right general direction, a feature which some cities like Baltimore entirely lacked, this would prove very difficult. The Appalachians, moreover, presented a daunting obstacle to an all-water route to the west. Tunnels could bore through high ground, locks and inclines could lift boats over it, but all at a formidable cost. And even with horse traction (which remained common throughout the 1830s), rail wagons could travel faster than a towed canal boat. So, by 1830, several railways (such as the Baltimore & Ohio, or B&O, intended to link the city to the river of that name, though it would take over two decades to do so) began to stretch westward.

Some cities that had already launched canal companies switched over to rail as events in Britain made the practicability of the technology clear. Pennsylvania, despite having already invested heavily in canals, abandoned a plan to connect the Delaware and Susquehanna by canal based on intelligence from England. William Strickland, a disciple of Henry Latrobe who visited England in 1825 to learn about the latest developments in transportation, advised the government that railroads were the future, so they instead backed an eighty-two-mile railroad from Philadelphia to Columbia.[4]

In the early years, American rail technology depended heavily on engineers like Strickland who had traveled to Britain to learn about locomotive and railroad design. The first major rail lines in Massachusetts, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Maryland all imitated the techniques used to construct the Liverpool and Manchester line in England.[5] To the extent that these early railways were steam-powered, they also relied mostly on locomotives imported from Britain or modeled on British exemplars. Many early American locomotives either came straight from the workshop of George and Robert Stephenson in Newcastle, or copied the design of the Stephensons’ Samson or Planet locomotives.[6]

Three factors gradually shunted American railroad technology off onto a different track from that of its British forebears: the presence of the Appalachians, the relative dearth of capital and labor west of the Atlantic, and the abundance there of cheap land and timber. The dominant railway pattern in Britain consisted of heavily graded routes made as flat and straight as possible, with gentle curves that both kept the locomotive and wagons secure on the tracks and minimized the cost of land acquisition. They were built to last, with bridges and viaducts constructed of sturdy stone and iron.[7] The same kind of construction could be found in the early railways on the eastern seaboard: the Thomas Viaduct, for example, on the B&O line, spanned (and still spans) the Patapsco River on arches of solid masonry.

But American builders could not afford to take the same approach as they moved westward, crossing the high mountains and vast distances required to reach the small towns of the Ohio valley and other points west. The United States for the most part still embodied the Jeffersonian ideal of a rural, agrarian society, and especially so in the west, where only 7% or so of the population lived in towns. Larger cities with a wealthy merchant class, a robust banking system, and capital to spare existed only on the coasts.[8]

A scrappier approach would be needed to make railways work in this context. Cheap construction trumped all other factors. In the early years, builders frequently resorted to flimsy “strap-iron” rails, consisting of a thin veneer of iron nailed to a wooden rail. They avoided expensive tunnelling or levelling operations to cross hills or mountains in favor of steeper gradients and tighter curves: by 1850, the U.S. had dug only eleven miles of railway tunnels compared to eighty in Britain, despite having several times Britain’s total track mileage by that point, much of which crossed mountainous terrain. As rails moved westward, American rail builders figured out how to construct bridges of timber trusses, a material readily available in the heavily wooded Ohio Valley, rather than iron or heavy stone construction like the Thomas Viaduct.[9]

The steep grades and sharp curves of American railways required changes to locomotive design: more powerful engines to haul loads up steeper slopes, and swiveling wheels for navigating turns without derailing. In 1832, John B. Jervis, chief engineer for New York’s Mohawk and Hudson Railroad, devised a four-wheeled truck for the front of his locomotive, which could rotate independently of the main carriage, allowing the locomotive to turn through might tighter angles. Other builders quickly copied the idea. Matthias Baldwin of Philadelphia, who went on to become the most prolific builder of American locomotives, had modeled his first (1831) locomotive on the Stephenson Planet. By 1834, however, he had developed a new design that incorporated Jervis’ bogie, a design that he would sell by the dozen over the next decade.[10] A few years later, a competing Philadelphia locomotive builder, Joseph Harrison Jr., developed the equalizing beam to distribute the weight of the vehicle evenly over multiple axles. This opened the way to locomotives with four or more driving wheels, providing the power needed to ascend mountain grades.[11]

Iron Rivers

One of the defining processes of modern times has been the decoupling of humanity from the cycles and contours of the natural world, contours and cycles that shaped its existence for millennia. Steam power, as we have seen before, abetted this process by providing a free-floating source of mechanical power, using energy “cheated” from nature by drawing down reserves of carbonaceous matter stored up for eons underground.

The course of rivers and streams, which had guided human settlement since humans began settling, provide a case in point. A river provides a source of drinking water and a natural sewer, but also a highway for travel and trade. Since before recorded history, people had moved bulk goods (such as food, fodder, fuel, timber, and ore) mainly by water.

The steamship allowed people to exploit such waterways more intensively, but then rail lines appeared and extended existing watersheds, acting as new tributaries. Finally, the main-line railroads that emerged by mid-century created artificial iron rivers, entirely independent of water, draining goods from their catchment area out to a major commercial hub where they might find a buyer.[12] As these rails reached westward in the United States, they also drained the life out of the steamboating trade, which faded to a shadow of its former self. Trains ran several times faster, followed the straightest course possible from town to town, and—unaffected by drought, flood, or freeze—operated year-round in virtually any weather.[13] Efficient, reliable, and immune from the whims and cycles of nature, they were modernity incarnate. As Mark Twain reflected in 1883, on revisiting St. Louis for the first time in decades:

…the change of changes was on the ‘levee.’ …Half a dozen sound-asleep steamboats where I used to see a solid mile of wide-awake ones! This was melancholy, this was woeful. The absence of the pervading and jocund steamboatman from the billiard-saloon was explained. He was absent because he is no more. His occupation is gone, his power has passed away, he is absorbed into the common herd, he grinds at the mill, a shorn Samson and inconspicuous.[14]

By the 1880s major riverfront cities such as Cincinnati and Louisville, cities that owed their existence to the Ohio river trade, cities molded by the millennia-old pattern of waterborne commerce, spurned the natural highway that lay at their feet. They shipped out some 95% of their goods—from cotton and tobacco to ham and potatoes—by rail.[15]

The steamboat had clearly lost out. But in the long run, none of the also-ran cities of the eastern seaboard—such as Baltimore, Philadelphia and Charleston—gained much on their peers from their investments in the railroad, either. New York continued to dominate them all. Instead, the biggest winner of the dawning American rail age emerged at the junction of the new iron rivers of the Midwest; a vast new metropolis was rising from the mudflats of the Lake Michigan shoreline on the back of the railroad.

Player With Railroads

Rivers and harbors had given life to many a great metropolis over the millennia; Chicago was the first to be quickened by rails. Not that water had nothing to do with it: Chicago’s small river ran close to the watershed of the Illinois River, giving it huge potential as a water link that could connect shipping flows on the Mississippi River system to the Great Lakes (and thus, via the Erie Canal, New York, the commercial nexus of the entire country). In the 1830s, Chicago was still a muddy little trading entrepot, its hinterlands recently wrested from the Potawatomi Indians, but a speculative real estate bubble took off on the assumption that it would explode in importance once a canal was built to connect the two water systems.[16]

That bubble collapsed with the crash of 1837, and the hoped-for canal did not finally appear until April 1848, with the help of the state and federal government.[17] By that time, the first of the railroads that would soon overshadow the canal in economic and cultural importance had already begun construction. The Galena and Chicago Union was overseen by Chicago bigwigs, but funded mainly by farmers along the proposed route, who opened their pockets in the (justified) belief that a railroad would drive up the value of their crops and their lands. By the start of the Civil War, The Galena and Chicago formed just one part of a vascular system of rails fanning out from Chicago across Illinois and southern Wisconsin to various points on the Mississippi—Galena to the northwest, Rock Island west, and Quincy southwest—that brought farm produce from the hinterlands into the city and returned with manufactured goods—like the new, Chicago-made, McCormick Reaper.

These lines formed the first of two different “railsheds” that served Chicago. The other, owned and operated mostly by eastern capital, consisted of a series of parallel trunk lines that formed an arterial connection to the cities of the east, especially New York. The base of Lake Michigan—a barrier, rather than a highway, from the point of view of the railroads—served as a choke point that brought both of these rail systems to Chicago. Competition among the various entering lines (and, in the ice-free months, with lake traffic for bulk goods), kept rates low and furthered Chicago’s advantages. The western rail system gathered in the products of the plains and prairies of the West–grain, livestock, and timber—while the eastern system disgorged it en masse to hungry markets. The city in between served as middleman, market maker, processor, storehouse, and more: “Hog Butcher for the World,\Tool Maker, Stacker of Wheat,\Player with Railroads and the Nation’s Freight Handler.”[18]

Chicago’s rival as gateway to the West, St. Louis, had long served as the concentration point for goods flowing from the territory north and west of it along the Mississippi and Missouri rivers, the former stomping grounds of Lewis and Clark. But as the Chicago railroads reached the Mississippi, they siphoned that traffic off to the east, starving St. Louis of commercial sustenance.

The rivermen fought a brief rear guard action in the mid-1850s: they tried to block the railroads from spreading further west by having the Chicago and Rock Island bridge across the Mississippi declared a hazard to navigation in 1857. Future president Abraham Lincoln traveled to Chicago to spearhead the case for the defense, and secured a hung jury, which was, practically speaking, a victory for the railroad interests.[19] Towns like Omaha, Nebraska, which might have naturally oriented their trade downriver to Missouri, now looked east. As one correspondent reported circa 1870, “Omaha eats Chicago groceries, wears Chicago dry goods, builds with Chicago lumber, and reads with Chicago newspapers. The ancient store boxes in the cellar have ‘St. Louis’ stenciled on them; those on the pavement, ‘Chicago.’”[20]

St. Louis was not the only party to suffer from the westward expansion of the railroads, however, and its fate was farfrom the bleakest.

Annihilating Distance

In the Mexican-American war of 1846-1848, the United States had acquired vast new territories in the West, including Alta (upper) California, on the Pacific coast. Then, shortly thereafter, James Marshall found flecks of gold in the waters of the sawmill he had established in the hills east of Sutter’s Fort, site of the future city of Sacramento. Word of wealth running in the streams drew the desperate, foolish, and cunning to the new territory by the hundreds of thousands. For those on the Atlantic seaboard, the fastest route to instant riches required two steamer legs in the Gulf of Mexico and the Pacific, bridged by a short but difficult crossing of the malarial isthmus of Panama; this could be done in a month or two if the steaming schedules lined up favorably. The sea journey clear round the southern tip of South America and back took two or three times as long, but avoided the risks of tropical disease. The direct landward journey offered the worst of both worlds: it took just as much time as the Cape Horn route with the added risk of death by illness or injury, along with the nagging fear of Indian attack. Only those who could not afford sea passage chose to go this way.[21]

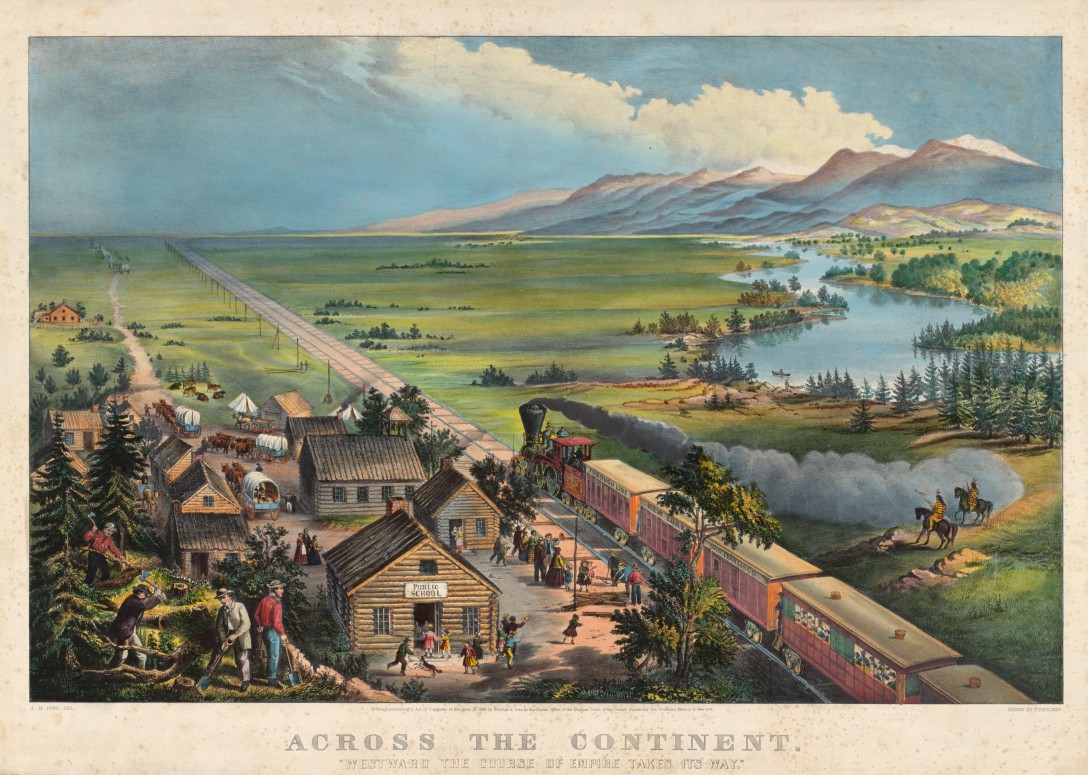

As California’s population boomed and Pacific trade began to expand, any American with a lick of avarice could see that great profit would be derived from a safer and more reliable means of reaching the Pacific, that transcontinental rail links would provide the best such means, and that—treaties and other promises notwithstanding—the natives living along the way would have to be pushed aside in the name of progress.

That work began in earnest in the mid-1850s. The Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, best known for its calamitous escalation of the rising tensions over slavery that would soon engender Civil War, originated in the desire of rail promoters like senator Stephen Douglas of Illinois to open a route to the west. Douglas preferred a route through Nebraska along the flatlands of the Platte River valley, but that was treaty-bound Indian Territory, designated for tribes such as the Kickapoo, Delaware, Shawne, and others. No investors would touch a railroad company that did not pass through securely white-controlled land, and so the Indian Territory would have to give way to new American territories, Kansas and Nebraska. Those previously living there could either decamp to parts still further west or be herded into the last remnant of the Indian Territory in Oklahoma. Anyone paying attention could foresee that neither refuge would stay a refuge for long.[22]

The machinations involved in planning and funding the trans-continental route were extensive enough to fill entire books. The Civil War provide the crucial impetus to end the talking and start the building, because the federal government no longer needed to take Southern opinion into account in its planning. As Douglas had advocated, the route began at the junction of the Platte with the Missouri River at Omaha and stretched west across plains and mountains to Sacramento, the epicenter of the Gold Rush. Despite a handful of raids that damaged equipment or killed small parties of workers or soldiers, the Cheyenne, Sioux and other tribes that lived in the area could do little to impede the coming of the iron road, which could count on the protection of the U.S. Army. In addition to providing military cover, the government made the whole enterprise worthwhile for the railroad companies (the Central Pacific and Union Pacific) by allotting them generous land grants along the right-of-way which they could sell to farmers or borrow against directly.[23]

The presence of the new rail route, along with numerous other lines that sprouted up across the West (often with land grants of their own), then accelerated further dispossession. They brought western lands into easy reach of eastern or immigrant settlers, and made those lands attractive by providing a way for those settlers to get their farm produce to market. The railroads also brought destruction to the keystone resource on which the livelihood of the equestrian tribes of the Great Plains depended. For decades, trains had carried domesticated livestock to urban slaughterhouses; the new lines across the Great Plains now made it profitable for white hunters to slaughter the bison herds of the plains in situ and then send their robes east by rail.[24]

Railroad Time

North America became a continent bound by steam; to the detriment of some but the great good fortune of others. By 1880, a rail traveler in Omaha could reach not just Sacramento, but also Los Angeles, Butte, Denver, Santa Fe, and El Paso. By 1890, the white population spreading along these rails had so completely covered the West that a distinct frontier of settlement ceased to exist.[25]

Nothing better symbolizes the transformation of the United States into a railroad continent (not to mention the general power of steam to supplant natural cycles with those convenient to human economic activity) than the dawn of railroad time. In the early 1880s, the country’s railroad companies exercised their power to change the reckoning of time across the entire continent, and, for the most part, their change stuck.

Traditionally, localities would set their clock to the local solar noon: the time when the sun stood highest in the sky. But this would not do for rail networks that spanned many stations; trains, unlike any earlier form of travel, could be scheduled to the minute, and they needed a standard time to schedule against. So, each rail company began keeping their own rail time (synched to the city where they were headquartered) which they used across all of their stations: in April 1883, forty-nine distinct railroad times existed in the United States. [26]

In that same month, William F. Allen, a railroad engineer, put forth a proposal to a convention of railroad managers to standardize the entire U.S. rail system on a series of hour-wide time zones. This would satisfy various pressures: from scientists for a system of time they could use to align measurements across the country and the globe, from state governments for more uniform time standards, and from travelers for easier-to-understand timetables. Britain had already adopted Greenwich Mean Time as their national time for similar reasons (and by a similar process – it had begun as a country-wide railway time in 1847 before being adopted by the government in 1880). The companies duly implemented the system in November 1883, and by March of the next year, most of the major cities in the U.S. had adjusted their clocks to conform to the new railroad time system.[27]

We have, by now, wandered a good way down the stream, exploring the consequences of the steamboat and locomotive, the most romantic and striking symbols of the age of steam. At this point we must make our way back up to the central channel of our story, resuming the story of the development of the technology of the steam engine, the prime mover itself.

[1] Max E. Gerber, “The Steamboat and the Indians of the Upper Missouri,” South Dakota History 4, 2(1974), 139-160.

[2] The U.S. had 380 miles in 1833 and 2,800 in 1840, versus 378 miles in 1836 and 2,210 miles in 1844 in Britain. Association of American Railroads, “Chronology of America’s Freight Railroads” (https://www.aar.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/AAR-Chronology-Americas-Freight-Railroads-Fact-Sheet.pdf); UK Parliament, “Railways in early nineteenth century Britain” (https://www.parliament.uk/about/living-heritage/transformingsociety/transportcomms/roadsrail/kent-case-study/introduction/railways-in-early-nineteenth-century-britain)

[3] Albert J. Churella, The Pennsylvania Railroad, Volume 1: Building an Empire, 1846-1917 (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013), 10.

[4] Churella, 42; Earl J. Hydinger, “The English Influence on American Railroads,” The Railway and Locomotive Historical Society Bulletin 91 (October 1954), 12.

[5] Darwin H. Stapleton, “The Origin of American Railroad Technology, 1825-1840,” Railroad History 139 (Autumn 1978), 66.

[6] M. N. Forney, “American Locomotives and Cars,” in Thomas Curtis Clarke, et. al., The American Railway: Its Construction, Development, Management, and Appliances (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1889), 4, 106-107; John H. White, Jr., “Old Ironsides, Baldwin’s First Locomotive,” The Railway and Locomotive Historical Society Bulletin 118 (April 1968), 85.

[7] Wolfgang Schivelbusch, The Railway Journey: The Industrialization of Time and Space in the 19th Century (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1977), 96.

[8] Mark Overton, Agricultural Revolution in England: The Transformation of the Agrarian Economy, 1500-1850 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996), 137-138; Jeremy Attack, et. al., “Did Railroads Induce or Follow Economic Growth? Urbanization and Population Growth in the American Midwest, 1850-1860,” Social Science History 34, 2 (Summer 2010), 171-197.

[9] Thomas Curtis Clarke, “The Building of a Railway,” in Thomas Curtis Clarke, et. al., The American Railway: Its Construction, Development, Management, and Appliances (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1889), 4-8, 27-29; Christian Wolmar, The Great Railroad Revolution: The History of Trains in America (New York: Public Affairs, 2012), 45-47.

[10] Baldwin Locomotive Works, History of the Baldwin Locomotive Works, 1831-1920 (Philadelphia: Baldwin Locomotive Works, 1920), 15-17; National Museum of American History “Model of the Philadelphia and Columbia Railroad’s Lancaster,” (https://americanhistory.si.edu/collections/search/object/nmah_1302459).

[11] Baldwin Locomotive Works, History, 26-27.

[12] Colonial railroads of course did the same, allowing the European states to stretch their logistical reach beyond the natural waterways where steam gunships had exerted power.

[13] Louis C. Hunter, Steamboats on the Western Rivers: An Economic and Technological History (New York: Dover, 1993 [1949]), 584.

[14] Mark Twain, Life on the Mississippi (Boston: James R. Osgood and Company, 1883), Chapter 22 (https://www.gutenberg.org/files/245/245-h/245-h.htm).

[15][15] Hunter, Steamboats on the Western Rivers, 602-603.

[16] William Cronon, Nature’s Metropolis: Chicago and the Great West (New York: W. W. Norton, 1991), 29, 62-63.

[17] Cronon, Nature’s Metropolis, 64.

[18] Cronon, Nature’s Metropolis, 83-93.

[19] Cronon, Nature’s Metropolis, 296-299. Christian Wolmar, The Great Railroad Revolution: The History of Trains in America (New York: Public Affairs, 2012), 86-87.

[20] Quoted in John S. Wright, Chicago: Past, Present Future: Relations to the Great Interior, and to the Continent (Chicago, 1870), 33.

[21] Frederic L. Paxon, History of the American Frontier, 1763-1893 (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1924), 372-375.

[22] Paxon, History of the American Frontier, 431-436.

[23] Wolmar, Great Railroad Revolution, 147-150.

[24] Cronon, Nature’s Metropolis, 216-224.

[25] John K. Wright, ed., Atlas of the Historical Geography of the United States (Washington: Carnegie Institution, 1932), 135; Frederick J. Turner, “The Significance of the Frontier in American History,” 1893 (https://www.historians.org/about-aha-and-membership/aha-history-and-archives/historical-archives/the-significance-of-the-frontier-in-american-history-(1893)).

[26] Ian R. Bartky, “The Adoption of Standard Time,” Technology and Culture, 30, 1 (January 1989), 46.

[27] Bartky, “The Adoption of Standard Time,” 49-50.