The British empire of the nineteenth century dominated the world’s oceans and much of its landmass: Canada, southern and northeastern Africa, the Indian subcontinent, and Australia. At its world-straddling Victorian peak, this political and economic machine ran on the power of coal and steam; the same can be said of all the other major powers of the time, from also-ran empires such as France and the Netherlands, to the rising states of Germany and the United States.

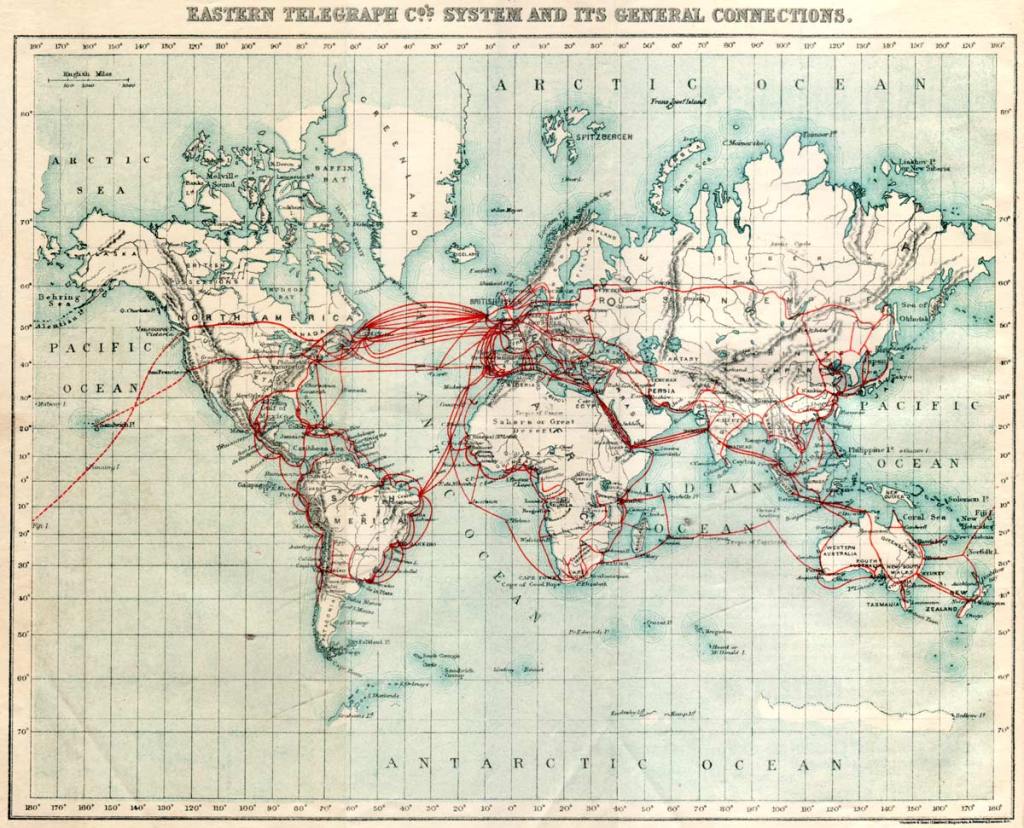

Two technologies bound the far-flung British empire together, steamships and the telegraph; and the latter, which might seem to represent a new, independent technical paradigm based on electricity, depended on the former. Only steamships, who could adjust course and speed at will regardless of prevailing winds, could effectively lay underwater cable.[1]

Not just an instrument of imperial power, the steamer also created new imperial appetites: the British empire and others would seize new territories just for the sake of provisioning their steamships and protecting the routes they plied.

Within this world system under British hegemony, access to coal became a central economic and strategic factor. As the economist Stanley Jevons wrote in his 1865 treatise on The Coal Question:

Day by day it becomes more obvious that the Coal we happily possess in excellent quality and abundance is the Mainspring of Modem Material Civilization. …Coal, in truth, stands not beside but entirely above all other commodities. It is the material energy of the country — the universal aid — the factor in everything we do. With coal almost any feat is possible or easy; without it we are thrown back into the laborious poverty of early times.[2]

Steamboats and the Projection of Power

As the states of Atlantic Europe—Portugal and Spain, then later the Netherlands, England, and France—began to explore and conquer along the coasts of Africa and Asia in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, their cannon-armed ships proved one of their major advantages. Though the states of India and Indonesia had access to their own gunpowder weaponry, they did not have the ship-building technology to build stable firing platforms for large cannon broadsides. The mobile fortresses that the Europeans brought with them allowed them to dominate the sea lanes and coasts, wresting control of the Indian Ocean trade from the local powers.[3]

What they could not do, however, was project power inland from the sea. The galleons and later heavily armed ships of the Europeans could not sail upriver. In this era, Europeans rarely could dominate inland states. When it did happen, as in India, it typically required years or decades of warfare and politicking, with the aid of local alliances. The steamboat, however, opened the rivers of Africa and Asia to lightning attacks or shows of force: directly by armed gunboats themselves, or indirectly through armies moving upriver supplied by steam-powered craft.

We already know, of course, how Laird used steamboats in his expedition up the Niger in 1832. Although his intent was purely commercial, not belligerent, he had demonstrated the that interior of Africa could be navigated with steam. When combined with quinine to protect European settlers from malaria, the steamboat would help open a new wave of imperial claims on African territory.

But even before Laird’s expedition, the British empire had begun to experiment with the capabilities of riverine steamboats. British imperial policy in Asia still operated under the corporate auspices of the East India Company (EIC), not under the British government, and in 1824 the EIC went to war with Burma over control of territories between the Burmese Empire and British India, in what is now Bangladesh. It so happened that the company had several steamers on hand, built in the dockyards of Calcutta (now Kolkata), and the local commanders put them to work in war service (much as Andrew Jackson had done with Shreve’s Enterprise in 1814).[4]

Most impressive was Diana, which penetrated 400 miles up the Irrawaddy to the Burmese imperial capital at Amarapura: “she towed sailing ships into position, transported troops, reconnoitered advance positions, and bombarded Burmese fortifications with her swivel guns and Congreve rockets.”[5] She also captured the Burmese warships, who could not outrun her and whose small cannons on fixed mounts could not effectively put fire on her either.

In the Burmese war, however, steamships had served as the supporting cast. In the First Opium War, the steamship Nemesis took a star turn. The East India Company traditionally made its money by bringing the goods of the East—mainly tea, spices, and cotton cloth—back west to Europe. In the nineteenth century, however, the directors had found an even more profitable way to extract money from their holdings in the subcontinent: by growing poppies and trading the extracted drug even further east, to the opium dens of China. The Qing state, understandably, grew to resent this trade that immiserated its citizens, and so in 1839 the emperor promulgated a ban on the drug.

The iron-hulled Nemesis was built and dispatched to China by the EIC with the express purpose of carrying war up China’s rivers. Shemounted a powerful main battery of twin swivel-mount 32-pounders and numerous smaller weapons, and with a shallow draft was able to navigate not just up the Pearl River, but into the shallow waterways around Canton (Guangzhou), destroying fortifications and ships and wreaking general havoc. Later Nemesis and several other steamers, towing other battleships, brought British naval power 150 miles up the Yangtze to its junction with the Grand Canal. The threat to this vital economic lifeline brought the Chinese government to terms.[6]

Steamboats continued to serve in imperial wars throughout the nineteenth century. A steam-powered naval force dispatched from Hong Kong helped to break the Indian Rebellion of 1857. Steamers supplied Herbert Kitchener’s 1898 expedition up the Nile to the Sudan, with the dual purpose of avenging the death of Charles “Chinese” Gordon fourteen years earlier and of preventing the French from securing a foothold on the Nile. His steamboat force consisted of a mix of naval gunboats and a civilian ship requisitioned from the ubiquitous Cook & Son tourism and logistics firm.[7]

Kitchener could only dispatch such an expedition because of the British power base in Cairo (from whence it ruled Egypt through a puppet khedive), and that power base existed for one primary reason: to protect the Suez Canal.

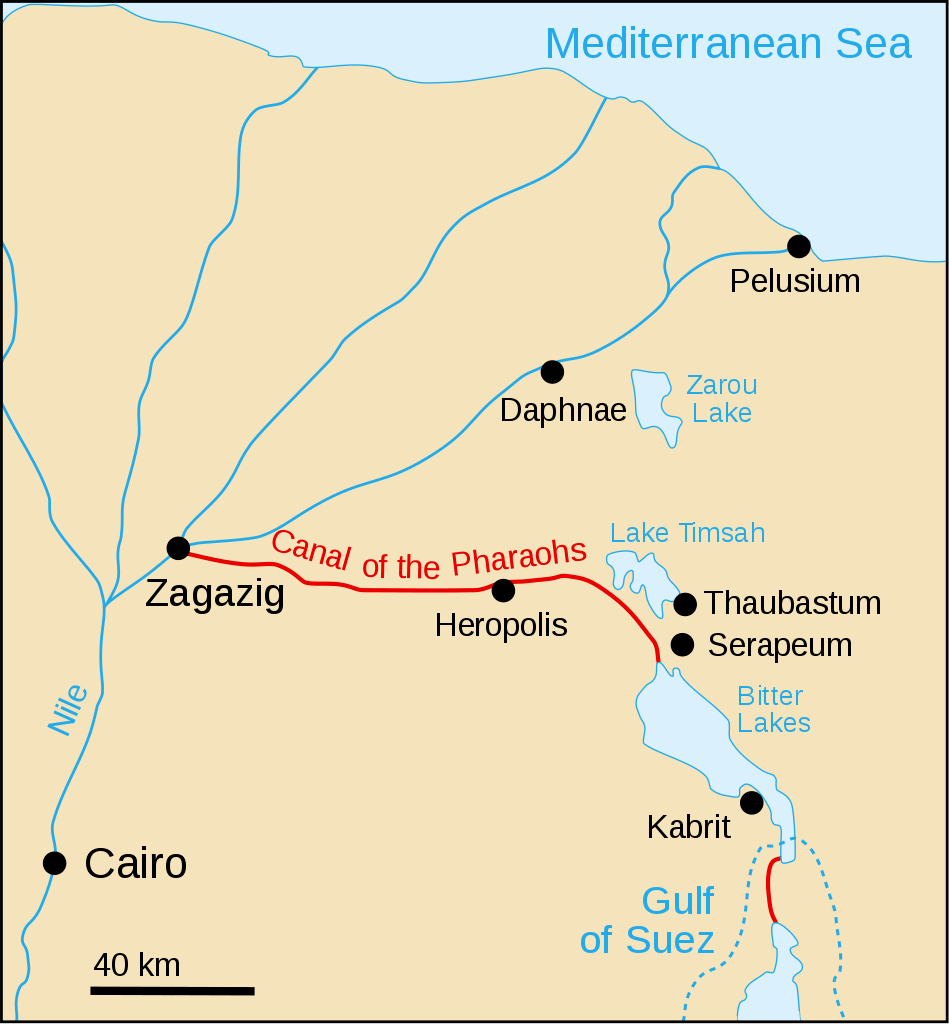

The Geography of Steam: Suez

In 1798, Napoleon’s army of conquest, revolution, and Enlightenment arrived in Egypt with the aim of controlling the Eastern half of the Mediterranean and cutting off Britain’s overland link to India. There they uncovered the remnants of a canal linking the Nile Delta to the Red Sea. Constructed in antiquity and restored several times after, it had fallen into disuse sometime in the medieval period. It’s impossible to know for certain, but when operable, this canal had probably served as a regional waterway connecting the Egyptian heartland around the Nile with the lands around the head of the Red Sea. By the eighteenth century, in an age of global commerce and global empires, however, a nautical connection between the Mediterranean and Red Sea had more far-reaching implications.[8]

Napoleon intended to restore the canal, but before any work could commence, France’s forces in Egypt withdrew in the face of a sustained Anglo-Ottoman assault. Though British commercial and imperial interests presented a far stronger case for a canal than any benefits France might have hoped to get from it, the British government fretted about upsetting the balance of power in the Middle East and disrupting their textile industry’s access to the Egyptian cotton cloth. They contented themselves instead with a cumbrous overland route to link the Red Sea and the Mediterranean. Meanwhile, a series of French engineers and diplomats, culminating in Ferdinand de Lesseps, pressed for the concession required to build a sea-to-sea Suez Canal, and construction under French engineers finally began in 1861. The route formally opened in November, 1869 in a grand celebration that attracted most of the crowned heads of continental Europe.[9]

It was just as well that the project was delayed: it allowed for the substitution, in 1865, of steam dredges for conscripted labor at the work site. Of the hundred million cubic yards of earth excavated for the canal, four-fifths were dug out with iron and steam rather than muscle, generating 10,000 horsepower at the cost of £20,000 of coal per month.[10] Without mechanical aid, the project would have dragged on well into the 1870s, if it were completed at all. Moreover, Napoleon’s precocious belief in the project notwithstanding, the canal’s ultimate fiscal health depended of the existence of ocean-going steamships as well. By sail, depending on the direction of travel and the season, the powerful trade winds on the southern route could make it the faster option, or at least the more efficient one given the tolls on the canal.[11] But for a steamship, the benefits of cutting off thousands of miles from the journey were three-fold: it didn’t just save time, it also saved fuel, which in turn freed more space for cargo. Given the tradeoffs, as historian Max Fletcher wrote, “[a]lmost without exception, the Suez Canal was an all-steamer route.”[12]

Ironically, the British, too conservative in their instincts to back the canal project, would nonetheless derive far more obvious benefit from it than the French government or investors, who struggled to make their money back in the early years of the canal. The new canal became the lifeline to the empire in India and beyond.

This new channel for the transit of people and goods was soon complemented by an even more rapid channel for the transmission of intelligence. The first great achievement of the global telegraph age was the transatlantic cable laid in 1866 by Brunel’s Great Eastern, whose cavernous bulk allowed it to lay the entire line from Ireland to Newfoundland in a single piece in 1866.[13] This particular connection served mainly commercial interests, but the Great Eastern went on to participate in the laying of a cable from Suez to Aden and on to Bombay in 1870, providing relatively instantaneous electric communication (modulo a few intermediate hops) from London to its most precious imperial possession.[14]

The importance of the Suez for quick communications with India in turn led to further aggressive British expansion in 1882: the bombarding of Alexandria and the de facto conquest of an Egypt still nominally loyal to the Sultan in Istanbul. This was not the only such instance. Steam power opened up new ways for empires to exert their might, but also pulled them to new places sought out only because steam power itself had made them important.

The Geography of Steam: Coaling Stations

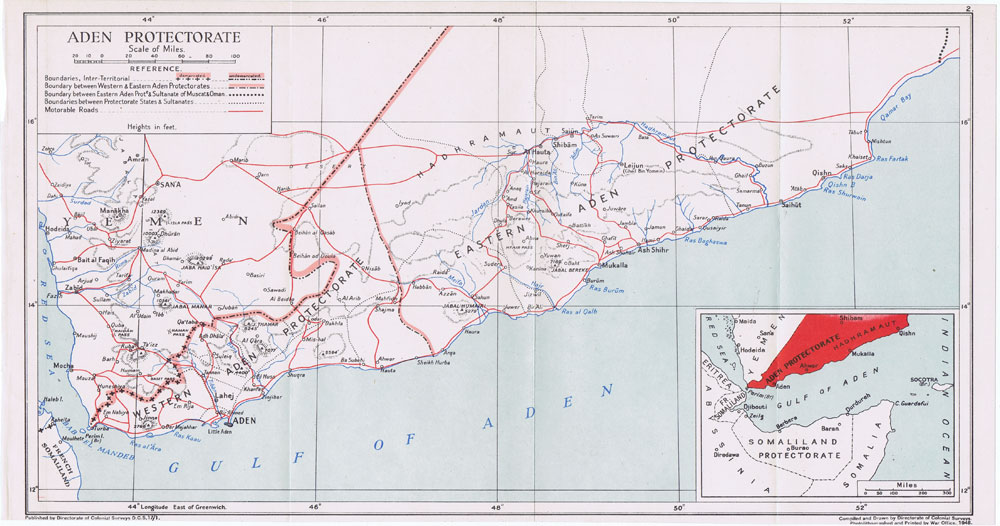

In that vein, coaling stations—coastal and island stations for restocking ships with fuel—became an essential component of global empire. In 1839, the British seized the port of Aden (on the gulf of the same name) from the Sultan of Lahej for exactly that purpose, to serve as a coaling station for the steamers operating between the Red Sea and India.[15]

Other, pre-existing waystations waxed or waned in importance along with the shift from the geography of sail to that of steam. St. Helena in the Atlantic, governed by the East India Company since the 1650s, could only be of use to ships returning from Asia in the age of sail, due to the prevailing trade winds that pushed outbound ships towards South America. The advent of steam made an expansion of St. Helena’s role possible, but then the opening of Suez diverted traffic away from the South Atlantic altogether. The opening of the Panama Canal similarly eclipsed the Falkland Islands’ position as the gateway to the Pacific.[16]

In the case of shore-bound stations such as Aden, the need to protect the station itself sometimes led to new imperial commitments in its hinterlands, pulling empire onward in the service of steam. Aden’s importance only multiplied with the opening of the Suez Canal, which now made it part of the seven-thousand-mile relay system between Great Britain and India. Aggressive moves by the Ottoman Empire seemed to imperil this lifeline, and so the existence of the station became the justification for Britain to create a protectorate (a collection of vassal states, in effect) over 100,000 square miles of the Arabian Peninsula.[17]

Coaling stations acquired local coal where it was available—from North America, South Africa, Bengal, Borneo, or Australia—where it was not, it had to be brought in, ironically, by sailing ships. But although one lump of coal may seem as good as another, it was not, in fact, a single fungible commodity. Each seam varied in the ratio and types of chemical impurities it contained, which affected how the coal burned.

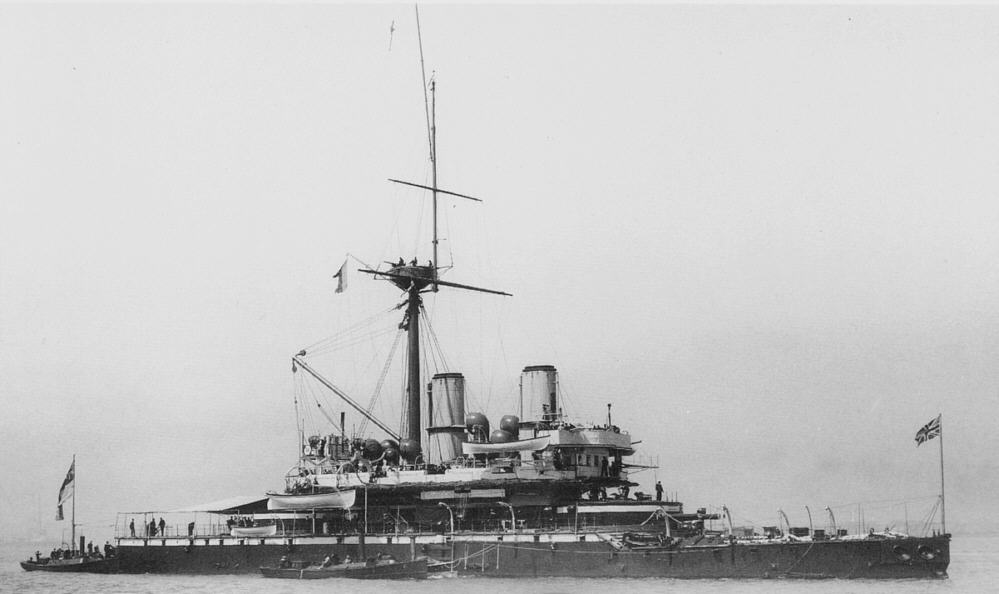

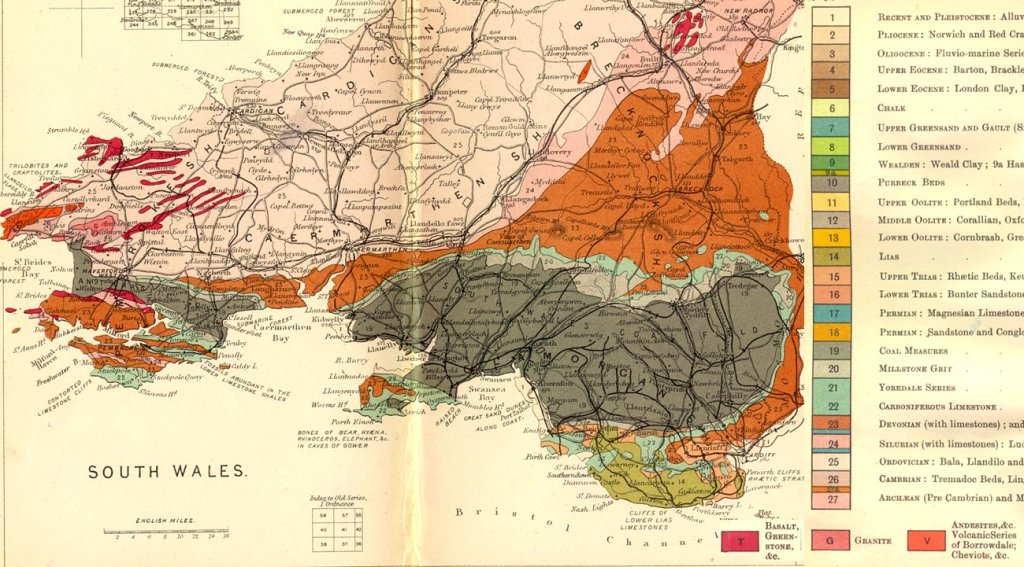

Above all, the Royal Navy was hungry for the highest quality coal. By the 1850s, the British Admiralty determined that a hard coal from the deeper layers of certain coal measures in South Wales exceeded all others in the qualities required for naval operations: a maximum of energy and a minimum of residues that would dirty engines and black smoke that would give away the position of their ships over the horizon. In 1871 the Navy launched its first all-steam oceangoing warship, the HMS Devastation, which needed, at full bore, 150 tons of this top-notch coal per day, without which it would become “the verist hulk in the navy.”

The coal mines lining a series of north-south valleys along the Bristol Channel, which had previously supplied the local iron industry, thus became part of a global supply chain. The Admiralty demanded access to imported Welsh coal across the globe, in every port where the Navy refueled, even where local supplies could be found.[18]

The British supply network far exceeded that of any other nation in its breadth and reliability, which gave their navy a global operational capacity that no other fleet could match. When the Russians sent their Baltic fleet to attack Japan in 1905, the British refused it coaling service and pressured the French to do likewise, leaving the ships reliant on sub-par German supplies. It suffered repeated delays and quality shortfalls in its coal before meeting its grim fate in Tsushima Strait. Aleksey Novikov-Priboi, a sailor on one of the Russian ships, later wrote that “coal had developed into an idol, to which we sacrificed strength, health, and comfort. We thought only in terms of coal, which had become a sort of black veil hiding all else, as if the business of the squadron had not been to fight, but simply to get to Japan.”[19]

Even the rising naval power of the United States, stoked by the dreams of Alfred Mahan, could scarcely operate outside its home waters without British sufferance. The proud Great White Fleet of the United States that circumnavigated the globe to show the flag found itself repeatedly humbled by the failures of its supply network, reliant on British colliers or left begging for low-quality local supplies.[20]

But if British steam power on the oceans still outshone that of the U.S. even beyond the turn of the twentieth century, on land it was another matter, as we shall next time.

[1] John Steele Gordon, A Thread Across the Ocean: The Heroic Story of the Transatlantic Cable (New York: Perennial, 2003), 59. Lewis Mumford, a twentieth-century theorist of technology, distinguished the coal-fired factory system of the paleotechnic age from the electrical diffusion of information and power in the neotechnic age.

[2] W. Stanley Jevons, The Coal Question: An Inquiry Concerning the Progress of the Nation, and the Probable Exhaustion of our Coal-Mines (London: Macmillan, 1865), vii.

[3] Geoffrey Parker, The Military Revolution: Military Innovation and the Rise of the West, 1500-1800, 2nd ed. (New York, Cambridge University Press, 1996), 104-108.

[4] Daniel Hedrick, The Tools of Empire: Technology and European Imperialism in the Nineteenth Century (New York: Oxford University Press, 1981), 20-21.

[5] Headrick, Tools of Empire, 21.

[6] Headrick, Tools of Empire, 47-53.

[7] Piers Brendon, Thomas Cook: 150 Years of Popular Tourism (London: Secker & Warburg, 1991), 234-35.

[8] Lord Kinross, Between Two Seas: The Creation of the Suez Canal (New York: William Morrow, 1969), 1-6.

[9] Headrick, The Tools of Empire, 150-156.

[10] Headrick, The Tools of Empire

[11] A. Le Gras, General Examination of the Mediterranean Sea: A Summary of its Winds, Currents, and Navigation (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1870), 144-148.

[12] Max E. Fletcher, “The Suez Canal and World Shipping, 1869-1914,” The Journal of Economic History 18, 4 (December 1958), 558.

[13] The Great Eastern laid several more Atlantic cables before being superseded by dedicated cable-laying ships that were far cheaper to operate. It ended its career as an advertising billboard and tourist attraction before being broken up for scrap in 1888. Bill Glover, “Great Eastern,” History of the Atlantic Cable & Undersea Communications (https://web.archive.org/web/20220630214952/https://atlantic-cable.com/Cableships/GreatEastern/index.htm)

[14] An overland route was available slightly earlier via Prussia, Russia, and the Ottoman and Persian empires, but service was unreliable and depended on the friendliness of several foreign governments. Dwayne R. Winseck and Robert M. Pike, Communication and Empire: Media, Markets, and Globalization 1860-1930 (Durham: Duke University Press, 2007), 34-38; Bill Glover, “The Evolution of Cable & Wireless, Part 2,” History of the Atlantic Cable & Undersea Communications (https://web.archive.org/web/20230430090144/https://atlantic-cable.com/CableCos/CandW/Eastern/index.htm).

[15] Headrick, The Tools of Empire, 136.

[16] H.V. Bowen, ”Afterword. Islands and the British Empire: From the Age of Sail to the Age of Steam” in Douglas Hamilton and John McAleer, eds., Islands and the British Empire in the Age of Sail (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2021), 200-201.

[17] R. J. Gavin, Aden Under British Rule: 1839–1967 (London, C. Hurst, 1975), 131-155.

[18] In later decades, high-quality New Zealand coal supplemented Welsh supplies in eastern depots. Steven Gray, Steam Power and Sea Power: Coal, the Royal Navy, and the British Empire, c. 1870-1914 (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018), 67-100; Jim Hargan, “The Life and Death of King Coal in South Wales,” The British Heritage Travel, July 13, 3016 (https://britishheritage.com/the-life-and-death-of-king-coal-in-south-wales).

[19] Gray, Steam Power and Sea Power, 125.

[20] Gray, Steam Power and Sea Power, 120-123.