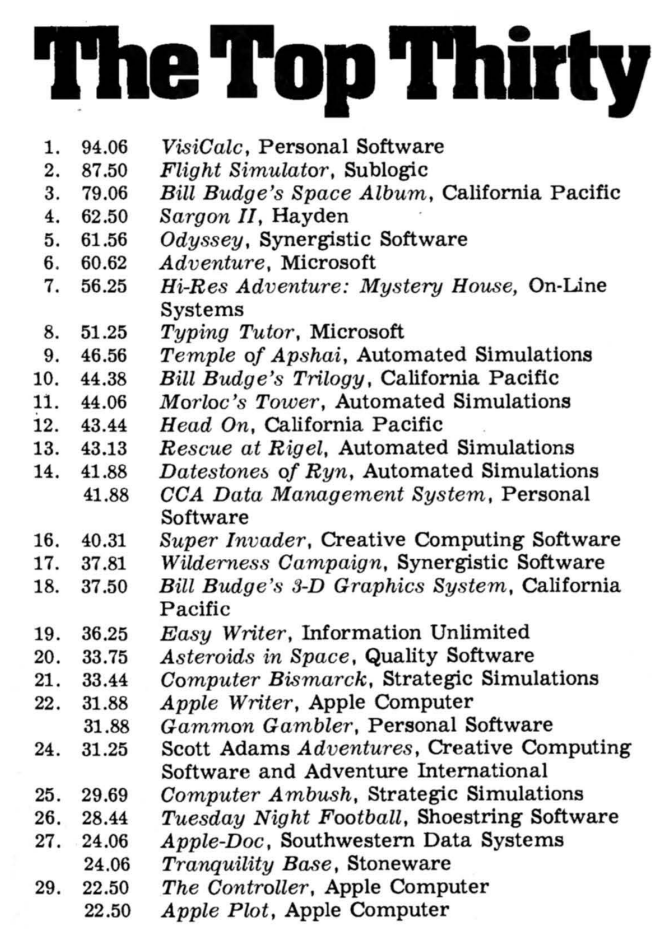

It’s difficult to say with certainty what the most popular titles or genres were in the early years of computer games. Many of the games were sold directly by mail-order, or through tiny single-proprietor stores, and no software trade organization was collecting comprehensive sales statistics. In 1980, the magazine Softalk began running a list of the top-thirty best-selling Apple II programs based on retailer surveys. It did not (and could not) provide absolute sales figures, but, although VisiCalc sat at the top, twenty-two of the titles were games. Most were CRPG, adventure, and arcade action games (including Automated Simulations’ Temple of Apshai, Sierra’s Mystery House, and a maze game called Head On). Microsoft Flight Simulator and the chess game Sargon II took second and fourth position, while the wargames Computer Bismarck and Computer Ambush, from Strategic Simulations, Inc. (SSI), could be found in the twenties.[1]

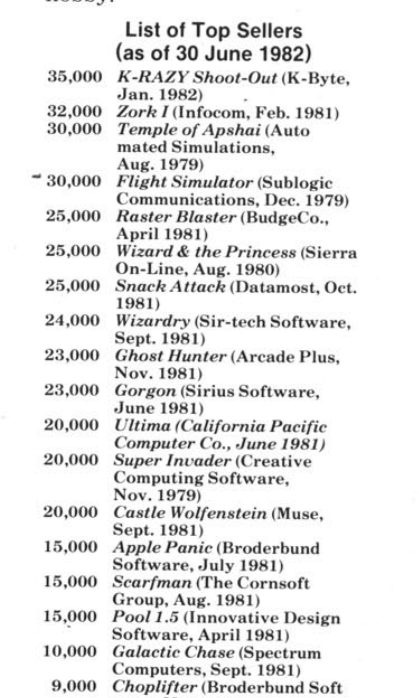

The earliest glimpse of hard numbers comes from a 1982 survey of software publishers by Computer Gaming World. Some firms refused to release sales numbers, but the highest selling title among those who did, the (now utterly forgotten) action game K-RAZY Shoot-Out, had sold 35,000 copies to date. Adventure and CRPG games made a strong showing: Infocom claimed 32,000 sales for Zork, Automated Simulations 30,000 for Temple of Apshai¸ Sierra 25,000 for The Wizard and the Princess, Sir-Tech’s Wizardry came in at 24,000 and Richard Garriot’s Ultima at 20,000.[2]

However, within the parallel universe of home video games, which had grown up simultaneously with but independently of personal computers, selling 30,000 units would hardly be something to brag about in 1982. Sales for hit video games regularly hit six or seven figures—Atari’s 1982 E.T., for example, which is retrospectively considered a flop because of excess production, nonetheless sold nearly two million copies.[3]

The lure of this massive market encouraged both video and computer game makers to create mass-market hybrid devices, typically called “home computers,” by combining the programmability and flexibility of a personal computer with the plug-and-play software cartridges of video game consoles. These third-generation personal computers (following the second-generation 1977 Trinity), were corporate creations—necessarily so, because where the second generation had wired together multiple off-the-shelf transistor-transistor logic chips to render the display or generate sounds, the home computers used dedicated, custom-made integrated circuits. Those bespoke hardware chips required a large capital investment to produce. The days of auteurs like Woz designing a new computer single-handedly from existing parts were over.[4]

The Origins of Home Video Game Systems

Atari began its existence in 1971 as Syzygy Engineering, a partnership between Nolan Bushnell and Ted Dabney with the goal of releasing a coin-operated version of the game Spacewar, created at MIT in the 1960s. They intended to put a digital foot in the electromechanical door of coin-operated amusements, a well-established industry, albeit one with a seedy reputation, associated in the public mind with gambling and the Mafia. Amusement makers manufactured everything from pinball games and shooting galleries to fortune tellers and love testers. Bars and restaurants would buy a machine or two to supplement their income, but there were also dedicated arcades whose entire revenue depend on the coin collectors of electromechanical amusements.[5]

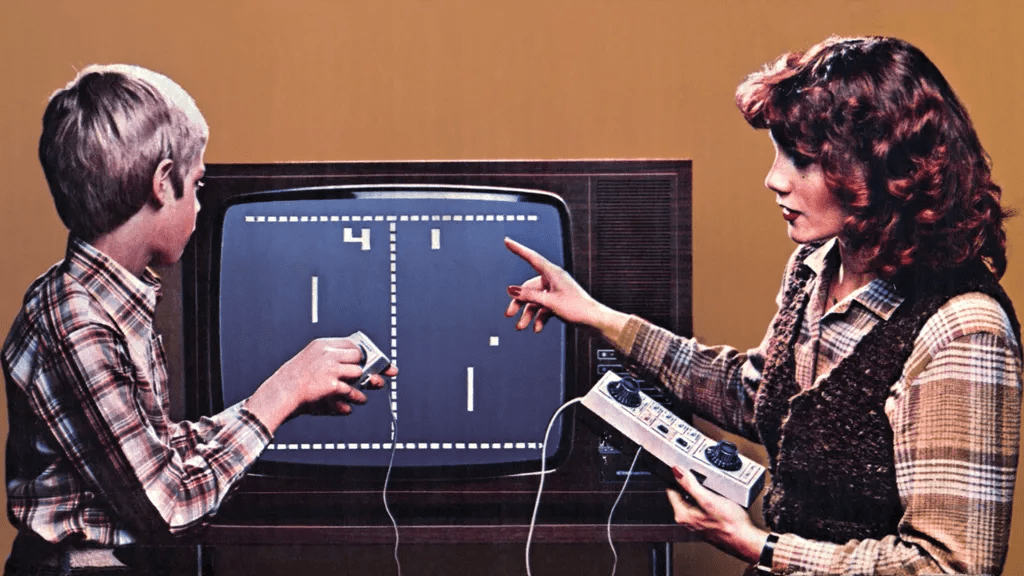

Meanwhile, in 1972, the television maker Magnavox released the first home video game system, the Odyssey, based on a concept conceived by Ralph Baer, an engineer at a New Hampshire defense contractor, back in 1966. The Odyssey could display only three dots and a line, and relied on plastic overlays stuck to the screen for most of its visual flair. Bushnell and Dabney (now calling themselves Atari) assigned newly-hired engineer Al Alcorn a starter project to learn the ropes of video games: recreate the Odyssey Ping-Pong game. Alcorn exceeded his remit and made a significantly improved game (adding a running score, extended paddles, and dynamic bounce angles), and the result was so fun that Atari turned his tutorial into a real product. Atari Pong became a smash arcade hit, selling 8,000 machines. With no moving parts outside the coin box, it was far easier to maintain than traditional amusements, and the shadowy reputation which had long clung to the industry failed to adhere to the modern sheen of the video game.[6]

Whereas the video games of the early 1970s were built out of many solid-state chips or components wired together, by 1974 Atari engineers realized that integrated circuits had gotten cheap enough to put a video game on a single chip, and package it for the home consumer market, with connectors to send the video signal to a television set, through the inputs normally used by the antenna. They designed a home version of Pong, and made a deal with Sears to release a white-label version for $99.95 for the Christmas 1975 season. The following year, semiconductor maker General Instruments released the AY-3-8500 chip, with built in circuitry for six different ball and paddle games, making it trivial for other companies to create their own Pong knock-offs. By Christmas 1977, thirteen of the seventy-four million households in the U.S. owned a Pong-type game: nearly eighteen percent. (In this same time period, from 1974 to 1977, Steve Jobs went from an Atari technician, hired as a teenager by Al Alcorn, to launching the Apple II.)[7]

The next logical step after putting a video game on a chipwas to use a standard microprocessor instead of designing custom logic for each game, and put the game in software, stored in a read-only memory (ROM) chip. This reduced production costs substantially because each game could use the same logic board, with only the programmable ROM swapped out. Arcade video games made the switch in 1975. But for home video games, the change to microprocessors also opened up another possibility – if the program ROM were interchangeable, then after selling the expensive core hardware once, you could get recurring sales from the same customer on high-profit-margin games. Other manufacturers beat Atari to the punch on this idea, putting the game ROM on a board that would slot into the game console that contained the microprocessor and other hardware, and then wrapping the board in a consumer-friendly plastic cartridge. First came Fairchild Semiconductor’s Video Entertainment System (later the Channel F) in late 1976, then RCA’s Studio II in early 1977. But Atari nonetheless took over the market in late 1977 with the $199 Video Computer System (VCS), a superior design to the chintzy, black-and-white-only Studio II with a better marketing and product strategy than the conservative, hardware-focused Fairchild.[8]

The home video game culture had little in common with the parallel home computer game culture. Playing a game on the VCS was a simple matter of turning it on and plugging in a cartridge. By contrast, Scott Adams’ Adventure came with a fifteen-step procedure for loading the game onto an Apple II, and additional multi-step sub-procedures for loading a saved game, and preparing a save game tape in the first place. This was pretty typical for games of the time: TRS-80 version of Temple of Apshai included a twelve-step start-up procedure (including a warning to expect a five-minute load time), and the first nine pages of the Zork manual are dedicated to disk procedures, with more details for certain special cases in an appendix. The style of the games themselves was also incomparable: as we have seen, the top of the computer game charts was heavy with complex and immersive adventure, role-playing and simulation games. Such games were not even possible to create on the VCS, which had hardly any memory, no more than four kilobytes of game data on ROM, and no ability to save progress between sessions. Most VCS games drew on the arcade tradition of fast-playing action and reflex games meant to keep the quarters coming.[9]

But…. the VCS used a MOS Technology 6507 processor, a variant of the 6502 that was used in the Commodore PET and Apple II. It was the same fundamental technology. The VCS proved you could sell a microprocessor-based platform for $199. What if you could make a full-fledged computer at a similar price point?

The First Hybrids

By June 1979, Atari had sold over one million VCS consoles. The 1980 port of the arcade game Space Invaders was Atari’s VisiCalc, driving huge numbers of console purchases. The Space Invaders cartridge ultimately sold six million copies. A Pac-Man port two years later sent sales even higher. Atari faced new competitors, such as Mattel’s Intellivision, but remained the undisputed champ of home video games well into the 1980s.[10]

But back in 1977, with VCS development nearing completion, Atari’s leaders could not know how durable and dominant it would prove to be. They expected the VCS to last for only three years or so, and felt the need to immediately start developing a successor. It was impossible not to notice the growing popularity of computers like the Commodore PET, Tandy/Radio Shack TRS-80, and Apple II. Making a successor to the VCS that combined its capabilities with those of the personal computer would allow Atari to tap into new markets and insulate itself from a total dependence on the fortunes of video games, which might fall as quickly as they rose. Anyone who was paying attention to the electronics business in the 1970s knew that it was easy-come, easy-go. One only had to look at citizens band (CB) radio, which had boomed in 1975 and 1976 but was already fading in popularity by 1977. But such business justifications also provided cover for the passions of the engineers: Joe Decuir, a computer enthusiast and Homebrew Computer Club member who helped design the VCS, had taken the job with the hope and expectation of working on an Atari computer next.[11]

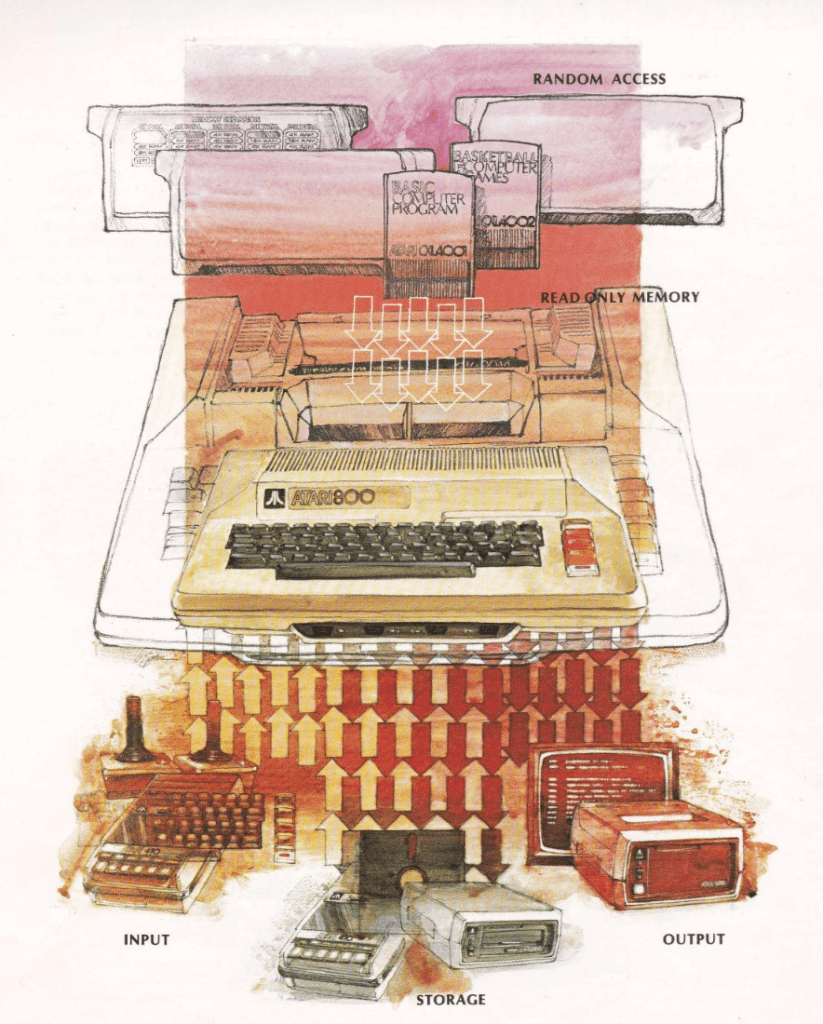

The VCS had effectively the same processor as a PET or Apple II, what it lacked was memory (the VCS had only 128 bytes of general-purpose RAM; the game instructions and data were read directly from the cartridge ROM), support for keyboard input and peripherals (most crucially, a disk drive or cassette player for external storage), and a BASIC programming language. Atari engineers came up with two models of computer, the low-end “Candy” and high-end “Colleen” (reputedly named after Atari secretaries), which became the Atari 400 and 800, collectively the Home Computer System (HCS), released in time for the 1979 Christmas season.[12]

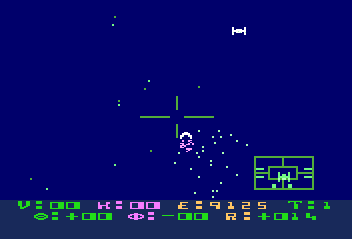

Containing a custom graphics chip with fourteen different display modes called ANTIC, the HCS line were first personal computers on the market that could compete with, and even surpass, the Apple II in color graphics. The POKEY audio chip also supplied the Atari computers with four-channel sound (the Apple II could render only single tones, and the original TRS-80 and PET had no built-in sound capability at all). From this palette, Atari engineer Doug Neubauer, designer of the POKEY chip, created Star Raiders. He placed first-person space-fighter combat inspired by Star Wars in a strategic framework of galactic war against a relentless enemy. The strategic layer, totally unheard of in arcade games at the time, derived from a computer game lineage: Neubauer copied it from one of the many Star Trek game variants on time-sharing systems and personal computers. At the same time, the real-time action exceeded most contemporary coin-op games in immersion, with hyper-drive star-stretching effects, debris from exploding enemy ships and, even a rear-view camera. It was another Atari hit.[13]

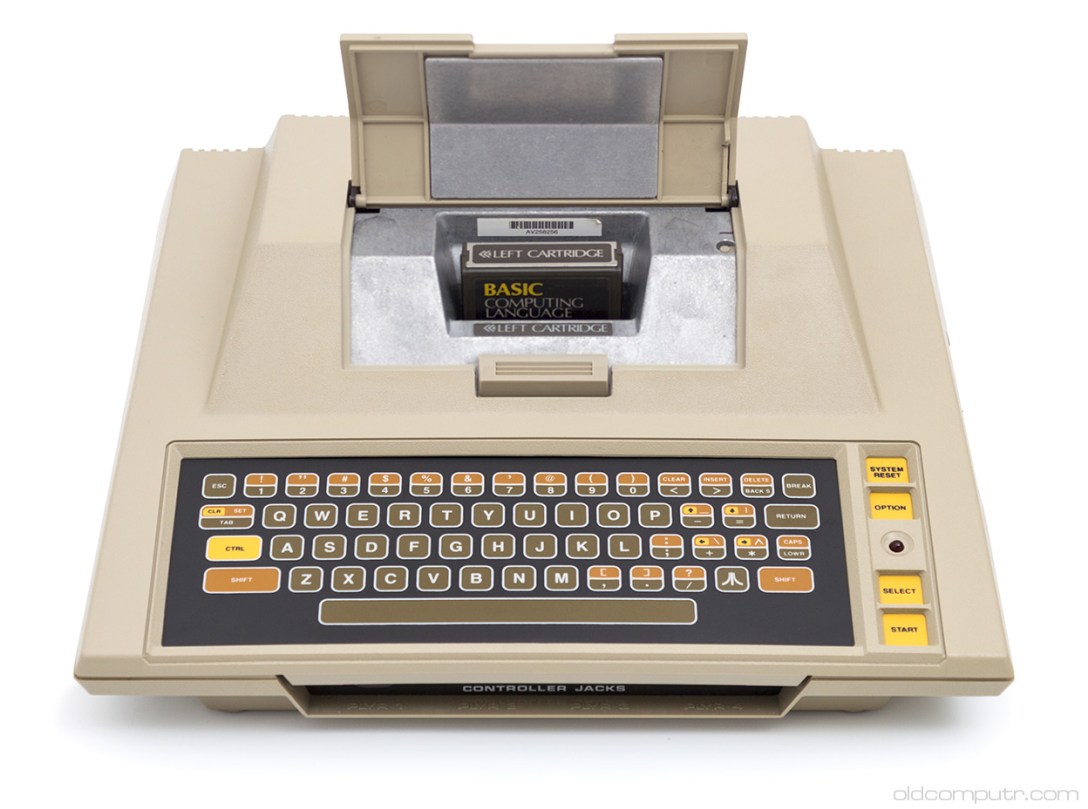

The low-end Atari 400 model cost only $550, but was saddled with an obnoxious membrane keyboard. The $1000 800, intended to compete with the likes of the Apple II, came with a real keyboard, two cartridge slots, a cassette storage peripheral, and a greater maximum memory capacity (up to forty-eight kilobytes). Both came equipped with eight kilobytes of memory and a BASIC programming cartridge. Sales rose steadily to a peak in 1982, when Atari sold 600,000 computers, two-thirds of them 400s, out-selling Apple and Radio Shack. Atari had skillfully blended the ease-of-use and dazzling audiovisual experience of a video game console with the expandability and programmability of a personal computer. The combination of top-notch graphics, cartridge slots, and four ports for joystick controllers made it the computer of choice in the early 1980s for game fanatics.[14]

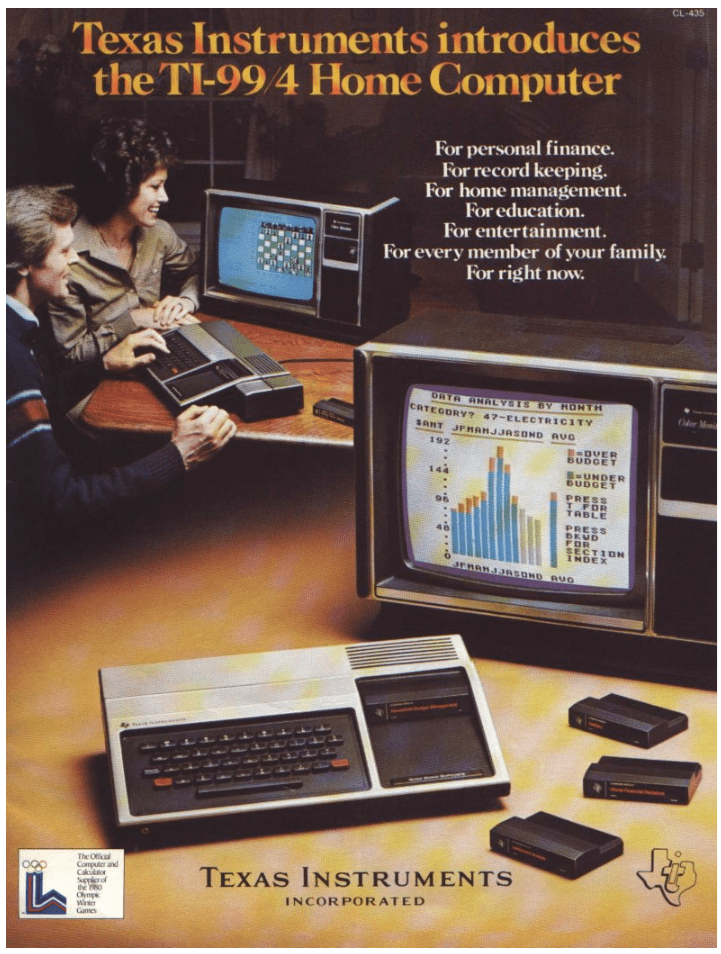

The HCS system immediately faced a competing product with similar design parameters, Texas Instruments’ TI-99/4: it, too, came with a dedicated graphics chip and a cartridge slot for software on ROM. But the 99/4 was as an expression of Texas Instruments’ corporate needs, not the needs of the market. It began with a failed microprocessor, the TMS9900. Texas Instruments (TI) had tried to leapfrog the 8-bit processor generation (which processed data in chunks of eight binary digits) and go straight to a 16-bit model, the 9900. (Up to this time, every personal computer used an 8-bit processor – typically a MOS 6502, Intel 8080, or Zilog Z80.) TI released their new technical marvel in 1976, but it found almost no buyers. The 9900 could support no more memory than its 8-bit competitors (all of which had a sixteen-bit memory addressing mode) and there were no supporting peripheral chips that operated at sixteen bits for it to connect to.[15]

TI leadership therefore decided to create an internal market for the processor by pushing it into a line of computer projects: a low-end $400 home computer/video game system (to serve a new “everyman” market segment), a mid-range programmable calculator, and a high-end business computer. After several rounds of corporate politics, only the home computer project survived. It was in the hands of the consumer products division (responsible for calculators and watches, and recently relocated to Lubbock, Texas) but under the leadership of the former head of the business computer project.[16]

Production delays meant that quantity production of the TI-99/4 didn’t start until early 1980, missing the 1979 Christmas season. But that was the least of the problems. Though the 99/4 had easy-to-use ROM software cartridges like the Atari VCS and HCS, at $1150, a similar price point to the Apple II, it was no hardly defining a new “everyman” market segment, even if the Atari 400 had not already existed. Like the PET and TRS-80, it supported only character graphics, not bitmapped graphics, though it at least supported full color. TI also equipped the 99/4 with the kind of calculator-style keyboard that computer buyers hated, because that’s what their consumer division was accustomed to working with. The sixteen-bit processor made it far more difficult for publishers to port software from other microcomputer models, but that hardly mattered, because no one else would be allowed to publish software for the 99-4. Texas Instruments intended to have total control over the software for its computers, and to reap all of the profits from selling ROM cartridges. Grown arrogant from their long string of consumer products successes (including 1978’s Speak and Spell), TI evidently felt they could dictate the terms for a new category without consideration for the existing, highly-competitive market for personal computers. The result was a colossal flop. Despite a $10 million investment, one estimate puts the 99-4’s total 1980 sales at 25,000 units, compared to 78,000 Apple IIs, 290,000 TRS-80s, and 200,000 Atari computers.[17]

An Aside on the FCC

Part of reason for the high price of the TI-99/4 was that it came with an included thirteen-inch color monitor. TI did this to comply with United States Federal Communications Commission (FCC) regulations on radio-frequency noise from home electronic devices. These regulations formed a background radiation field of their own, one that played a major role in the personal computer market of the late 1970s and early 1980s. The parameters in which personal computers could operate were framed by the cultural power of television.[18]

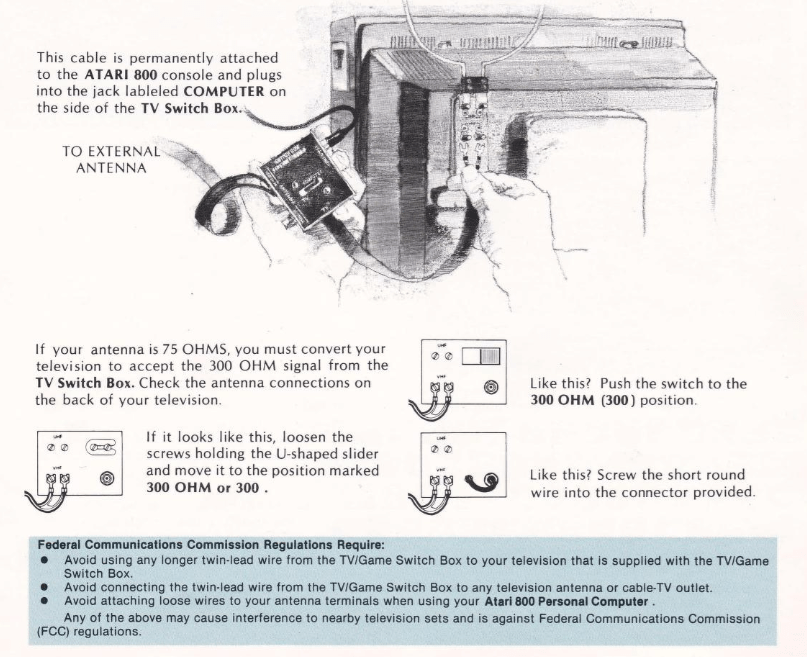

In 1972, the FCC issued new regulations for “Class I TV Devices.” They were motivated primarily by the emergence of home videotape recorders and players, but also explicitly considered “TV game devices,” such as the newly-released Odyssey. The high-frequency components inside electronic equipment generated electromagnetic radiation, which, if not properly shielded, would be picked up by anything antenna-like in or attached to the device (such as wires and cables) and broadcast as radio-frequency (RF) noise. The FCC wanted to protect consumers from noisy devices that would interfere with their television, or, more importantly, that of their neighbors, degrading or even completely decohering the image. The 1972 rules applied strict noise limits to any product designed to send to video signals to a television set, typically through an RF modulator: a device to modulate a video output signal onto a carrier wave of a frequency that could be received by a television set through the input terminals normally used for the antenna.[19]

The major personal computers released in 1977, however, all evaded these regulations. The Commodore PET and TRS-80, because they bundled a black-and-white television set in as part of the product. These were not Class I devices, because they did not attach to an external television set. Apple, on the other hand, pretended that their product didn’t have anything to do with television: the Apple II did not come with an antenna output at all. Apple designed an RF modulator, but gave the design to M&R Enterprises (whose owner Jobs and Woz knew through the Homebrew Computer Club), which then sold it with a wink as a third-party product, the Sup’R’Mod. Separately, neither product fell under Class I regulations, and nothing prevented computer stores from selling the customer both at the same time.[20]

Neither of these tacks was acceptable to the makers of hybrid computer / video game systems, Atari and Texas Instruments. They needed full-color output, and a bundled color television would add too much to the price of the computer. And they wanted to make a simple-to-use, everyman computer; asking the everyman to purchase and install a third-party peripheral card before their kids could start playing games on Christmas day was not going to fly. Atari believed, as engineer Al Alcorn put it, that Atari had an “unfair advantage” in this situation: the preexisting engineering capability to deal with the FCC’s electromagnetic noise regulations. Their Pong and VCS consoles, which used RF modulators to connect directly to televisions, already had to comply with the 1972 rules.[21]

But the problem with a computer intended to compete with the likes of the Apple II, as compared to a video game console, was that it would need to support a wide variety of peripherals. Apple did this with expansion cards that could connect to various devices (disk drives, printers, drawing pads, and so forth) through openings in the rear of the case. But these openings also leaked RF noise copiously. To meet the FCC standards, Atari did away with these open slots. The Atari computer would be entirely encased in metal shielding, and talk to the outside world through a shielded serial input-output (SIO) port. External peripherals would have to contain all the controller hardware that otherwise would go on an Apple II-style expansion board, and push any required control software up to the computer. Each peripheral also needed to expose its own SIO port so that multiple devices could link into the single SIO port on the computer in daisy-chain fashion, and it had to incorporate logic to identify which signals sent through the daisy chain were intended for itself, and which it should simply pass along. Atari had cracked the problem of FCC compliance for a fully expandable computer, and made peripherals incredibly easy-to-use compared to their competitors (they functioned much like modern plug-and-play USB devices). But they paid a substantial price: not only did the shielding drive up the hardware cost of the HCS, every peripheral would be much more expensive as well, with hardware custom-designed specifically for Atari computers.[22]

Texas Instruments also limited 99/4 peripherals to integrated ports, but, lacking the prior video game experience of Atari, their internal RF modulator for TV output failed to meet FCC standards, and the FCC refused their petitions to approve an external, stand-alone RF modulator or to waive the the Class I devices regulation for the 99/4. Hence the bundled color monitor, which accounted for a significant portion of the 99/4’s eye-watering $1150 price.[23]

Then, the landscape tilted. Since 1976, the FCC had been considering revisions to its rules in response to a variety of complaints about interference from computers and other electronic devices. In 1979, they finally acted, precipitated in part by Texas Instruments’ petitions, but also by the increasing cost of further delay due to a boom in personal computers that they could not have anticipated in 1976: “failure of the Commission to act immediately,” wrote the FCC’s secretary, “will mean that millions of personal computers may be sold over the next few years with little or no radio frequency suppression.” Though they made some gestures at concern about interference with public communications like police radio, it is clear from the process used to decide on appropriate limits that the overwhelming concern was with protecting television: the incidental noise emitted from computers could not be allowed to interfere with the broadcast communications that had become an essential part of the everyday lives of most Americans.[24]

The new rules the FCC issued in the fall of 1979 expanded the scope of RF noise regulation to include all personal computers, whether they hooked up to a television or not, and required manufacturers to file testing results for certification with the FCC prior to selling a new product. Originally intended to go into effect in July 1980, multiple extensions delayed full enforcement of the rules well into 1981. Still, there would be no more evading regulation by bundling in a monitor, or removing the antenna output from your product. Good news for Atari, it seemed: not only would Texas Instruments have to match Atari’s low-noise computer design, Radio Shack, Apple, and Commodore would as well. Butthere was a sting in the tail: the new regulations also increased the noise ceiling drastically, from fifteen microvolts per meter at one meter from the device to one hundred microvolts per meter at three meters. This new standard was so much easier to satisfy, that the FCC found that some extant personal computers, which had made no special efforts at noise suppression, were nonetheless already in compliance.[25]

It’s debatable whether Texas Instruments came out of all of this a winner (they would have been wiser to cut their losses and leave the computer business altogether), but Atari was certainly a loser. They had expected to outmaneuver their opponents on the regulatory field, but existing computer makers ended up having ample time to make the relatively modest changes needed to satisfy the new regulations, and the revised Apple II was able to keep its open slots while still staying in compliance. Atari, on the other hand, was stuck with their (now) over-engineered design for the HCS platform and its high-cost approach to peripherals. Very small hobby-entrepreneur computer makers were also losers; the new testing and certification requirements to show compliance with the standard posed a fixed cost on every computer model released, regardless of how many were sold, favoring economies of scale.[26]

With the new rules of the game established, and multiple players vying to exploit those economies of scale to the max in order to put a computer in every home, competition in the bottom end of the personal computer market was poised to ramp up. The stage was set for the home computer war.

[1] “Softalk Presents the Bestsellers,” Softalk (October 1980), 27 (https://vintageapple.org/softalk/pdf/SOFTALK_8010_v1_n02.pdf).

[2] Dana Lombardy, “Inside the Industry,” Computer Gaming World (September-October 1982), 2.

[3] Mona Chalabi, “Where Atari’s ‘E.T.’ Ranks Among Video Game Flops,” FiveThirtyEight (April 14, 2014) (https://fivethirtyeight.com/features/where-ataris-e-t-ranks-among-video-game-flops).

[4] I owe this insight to Paul Houle (https://news.ycombinator.com/item?id=44355648). The following source breaks down the details of how the Apple II graphics system was built from TTL: “Apple II graphics: More than you wanted to know,” Nicole Express (June 28, 2024) (https://nicole.express/2024/phasing-in-and-out-of-existence.html)

[5] Mark J.P. Wolf, “Arcade Games of the 1970s,” in Mark J. P. Wolf, ed.The Video Game Explosion: A History from PONG to Playstation and Beond (Westport: Greenwood Press, 2008) 35-44; Tristan Donovan, Replay: The History of Video Games (Lewes: Yellow Ant, 2010), 24-25.

[6] Donavan, Replay, 23-35.

[7] Donovan, Replay, 36; U.S. Census Bureau, “No. HS-12. Households by Type and Size: 1900 to 2002,” Statistical Abstract of the United States (2003), 19 (https://www2.census.gov/library/publications/2004/compendia/statab/123ed/hist/hs-12.pdf).

[8] Tristan Donovan, Replay: The History of Video Games (Lewes: Yellow Ant, 2010), 41-42, 66-68; Smith, They Create Worlds, 318-325, 329-334, 340-342.

[9] Adventure International, “Adventureland” (1980) (https://archive.org/details/Scott_Adams_Adventureland); Automated Simulations, “Special Instructions: The Temple of Apshai” (1979) (https://mocagh.org/loadpage.php?getgame=templeapshai-manual); Personal Software, “Zork: Radio Shack TRS-80 Model III” (1982) (https://archive.org/details/Zork_The_Great_Underground_Empire_1982_Infocom_a).

[10] “Atari Speaks Out,” Creative Computing (August 1979), 58-59; “List of best-selling Atari 2600 video games,” Wikipedia (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_best-selling_Atari_2600_video_games); Donovan, Replay, 89.

[11] Edwin McDowell, “C.B. Radio Industry Is More in Tune After 2 Years of Static,” New York Times (April 17, 1978); Benj Edwards, “How Atari Took On Apple in the 1980s Home PC Wars,” Fast Company (December 21, 2019) (https://www.fastcompany.com/90432140/how-atari-took-on-apple-in-the-1980s-home-pc-wars).

[12] Marty Goldberg and Curt Vendel, Aari Inc.: Business is Fun (Carmel, NY: Syzygy Company Press, 2012), 547-566; Steve Fulton, “Atari: The Golden Years — A History, 1978-1981,” Gamasutra (August 21, 2008) (https://web.archive.org/web/20080825070844/http:/www.gamasutra.com/view/feature/3766/atari_the_golden_years__a_.php); Benj Edwards, “How Atari Took On Apple in the 1980s Home PC Wars,”

[13] “ANTIC,” Wikipedia (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ANTIC); Jeffrey Fleming, “Video Games’ First Space Opera: Exploring Atari’s Star Raiders,” Game Developer (September 20, 2007). (https://www.gamedeveloper.com/design/the-history-of-i-star-raiders-i-taking-command).

[14] Jamie Lendino, Breakout: How Atari 8-Bit Computers Defined a Generation, 2nd edition(Steel Gear Press: Audubon, NJ, 2023),15. Jeremy Reimer, “Notes on Sources,” Jeremy’s Blog (December 7, 2012) (http://jeremyreimer.com/uploads/notes-on-sources.txt).

[15] Walden C. Rhines, “The Inside Story of Texas Instruments’ Biggest Blunder: The TMS9900 Microprocessor,” IEEE Spectrum (June 22, 2017) (https://spectrum.ieee.org/the-inside-story-of-texas-instruments-biggest-blunder-the-tms9900-microprocessor).

[16] Joseph Nocera, “Death of a Computer,” Texas Monthly (April 1984) (https://www.texasmonthly.com/news-politics/death-of-texas-instruments-home-computer). Walden Rhines, a former Texas Instruments executive, presents a different set of three internal TI computer projects and a different sequence – the projects came first and the mandate to use the TMS9900 after. My choice on which to trust was somewhat arbitrary. On the one hand, Rhines is a first-hand source, on the other hand the Texas Monthly article was written decades closer to the events in question, and presumably based on interviews with participants. Walden C. Rhines, “The Texas Instruments 99/4: World’s First 16-Bit Home Computer,” IEEE Spectrum (June 22, 2017) (https://spectrum.ieee.org/the-texas-instruments-994-worlds-first-16bit-computer).

[17] Nocera, “Death of a Computer”; Charles Good, “The 99/4 Home Computer: Description of an Antique,” (February 1991) (https://www.ti994.com/overview/goodarticle.html); Jeremy Reimer, “Total Share: Personal Computer Market Share 1975-2010,” Jeremy’s Blog (December 7, 2012) (https://web.archive.org/web/20190705092524/http:/jeremyreimer.com/rockets-item.lsp?p=137).

[18] There is a lot of confusion in the sources about the role and timeline of FCC regulation in personal computing history. I am obliged to several discussions in the Retro Computing community for helping me to establish what I believe to be the correct story, especially https://retrocomputing.stackexchange.com/questions/27428/did-atari-lobby-against-fcc-regulation-change, which points out the huge difference in noise levels between the 1972 and 1979 regulations.

[19] Federal Communications Commission, “FCC 72-1098,” in Federal Communications Commission Reports 38, 2nd series (1974), 436.

[20] M&R Enterprises is one of many forgotten hobby-entrepreneur shops of the early personal computer years. Founded by Homebrew Computer Club member Marty Spergel and his wife, Rona, it sold other computer peripherals, such as Lee Felsenstein’s Pennywhistle Modem, and even its own computer, the short-lived Astral 2000. Based on archive.org searches, they seem to have gone out of business in the mid-1980s. Levy, Hackers, 220, 266-267; Sheila Clarke, “A New Approach to the 6800… the Astral 2000,” Kilobaud (March 1977), 50-53. Apple did acknowledge other third-party television vendors: Apple, Apple II Reference Manual (January 1978), 112.

[21] “ANTIC Interview 32 – Al Alcorn, Atari Employee #3,” ANTIC The Atari 8-bit Podcast (April 12, 2015) (https://ataripodcast.libsyn.com/webpage/antic-interview-32-al-alcorn-atari-employee-3).

[22] Goldberg and Vendel, Atari Inc, 568-569.

[23] Charles Good, “The 99/4 Home Computer: Description of an Antique,” (February 1991) (https://www.ti994.com/overview/goodarticle.html). At the time, a 13-inch color television set retailed for about $300. A black-and-white model cost one-third as much. Sears, 1979 Sears Christmas Book (1979), 403, 409. (https://christmas.musetechnical.com).

[24] Federal Communications Commission, “47 CFR Parts 2 and 15,” Federal Register 46, 201 (October 16, 1979), 59535.

[25] Federal Communications Commission, “47 CFR Parts 2 and 15,” 59533; Federal Communications Commission, “FCC 72-1098,”, 438; Chris Brown and Eric Maloney, “FCC Takes Aim Against RFI Polluters,” Kilobaud Microcomputing (April 1981), 30.

[26] That’s not to say that achieving compliance was a totally trivial matter. In 1983, Apple had to redesign the Apple III after the initial version failed FCC compliance (but the failure of that product was overdetermined).