In the late 1960s and early 1970s, one could participate in a variety of (mostly novel) hobbies that all asked “what-if”: reading and watching science fiction (especially Star Trek), reading the writings of Tolkien and his growing body of imitators, playing tabletop war games that simulated everything from ancient warfare to World War II, engaging in the simulated medieval battles of the Society for Creative Anachronism (SCA), and imbibing the romanticized past of renaissance fairs. All opened the doors to the exploration of alternate worlds, alternate pasts, or possible futures, through the medium of the participants’ imagination. Not everyone who liked one of these things liked all of the others, but they formed a cultural cluster of frequently overlapping interests that tended to be favored by those who didn’t fit in to the mainstream social norms—that is to say, nerds. In the mid-1970s, the nerds found two new hobbies: personal computers, and Dungeons and Dragons (D&D).[1]

A game of “let’s pretend” with rules and dice, a game with no winners and losers and no definite ending, D&D broke with familiar ludic conventions. Those who hadn’t experienced it often struggled to understand or explain it. A 1979 New York Times article captures some of the essence, but also exposes some of the author’s confusions:

A leader, called the Dungeon Master, chooses from three rule books and draws elaborate maps of an imaginary dungeonlike maze. With a roll of the dice, the participants choose one of five roles they wish to play: elves, dwarves, halflings, humans or Hobbits. They verbalize their actions, with the leader throwing out challenges and the participants coming up with solutions. There are various endings — from survival and gaining power to being resurrected.[2]

In D&D players played the game indirectly, through the medium of a fictional character of a particular type (a fighting-man, say, or a magic-user), and inhabited the character’s role within the fictional sub-creation of the game, like an actor in a play. But if one of Dungeons and Dragons’ feet stood in this airy realm of imagination, the other was firmly planted in the combat charts and statistical profiles of its wargaming heritage: each character had a set of numerical characteristics that defined their capabilities in combat, magic, and other areas. Characters could advance in level (and therefore power) through successful adventures, typically delves into an underground lair to find treasure guarded by monsters and traps.

It was this latter, statistical face of D&D that became the defining feature of a new genre of computer game, the computer role-playing game (CRPG). While Adventure and some of its immediate successors borrowed their setting and goal (delving into a hole in he ground in search of treasure) from D&D, that genre quickly branched out into entirely different experiences that owed little to role-playing. Most adventure games gave the player a particular role within the game (a king in search of a princess, an investigator on the trail of a crime, etc.), but this owed more to fictional precedents than to D&D: Roberta Williams, for example, based Mystery House on Agatha Christie’s And Then There Were None, and it was natural to put the player in the role of the detective. Later adventure games usually gave the player control of a specific, named protagonist. As a general rule, CRPG characters were defined more by their in-game capabilities than by their fictional role in the narrative.

Also unlike adventure games, no single ur-CRPG defined the parameters of the genre. Many players of D&D independently came up with the idea of creating a digital simulacrum of the game, sometimes as an offshoot of writing software tools to help them administer their pen-and-paper games. Nor did they borrow a great deal from time-sharing precursors. One particular hothouse environment, the PLATO time-sharing system hosted at a few universities, harbored a flourishing CRPG ecosystem, with bitmapped graphics and online multiplayer support. These games would not be surpassed in every dimension until the mid-1990s. Few people outside the universities with PLATO access knew about these games, but they did influence one of the more significant early personal computer CRPGs, as we will see. Without a common template like Adventure on which to model themselves, the CRPGs of 1978-1980 varied greatly in design. D&D contained many game elements and potential play styles, from amateur theater role-play to mindless monster slaughter, each more or less adaptable to digital form, and by 1979 it also had many pen-and-paper offshoots, from variant rules like the Perrin Conventions and the Arduin Grimoire to entirely new role-playing games with totally different settings and core rules such as Traveller and Runequest.

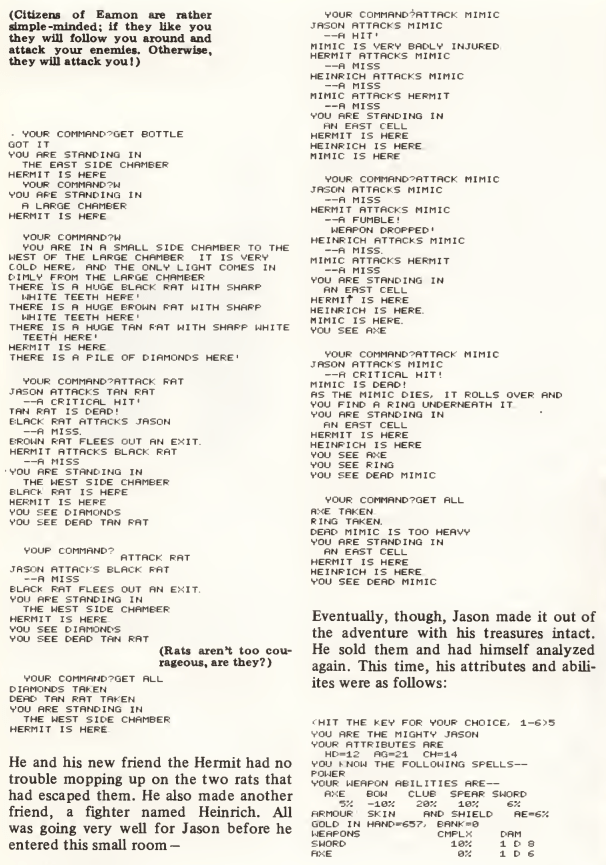

Because ex nihilo nihil fit, most of the earliest CRPGs started with a maze or adventure game framework, and added D&D elements. The code for Gary Shannon’s Dragon Maze, which challenged the player to escape a randomly generated maze before being eaten by a dragon, was printed in the Apple II Reference Manual, and became the basis for two 1978 CRPGs, Don Worth’s Beneath Apple Manor and Bill Clardy’s Dungeon Campaign. Both expanded upon Dragon Maze by adding multiple dungeon levels, monsters to fight, and treasure to find, though Apple Manor gave the player a single character with statistics like strength and intelligence, while Dungeon Campaign put the player in charge of a whole party of characters of varying types. Two years later, Donald Brown, an Apple II lover, D&D player, and SCA enthusiast in Des Moines, released Eamon at cost via the local Computer Emporium, and later through the Apple II user group. Built upon the backbone of text adventure games, it tracked the player character’s hardiness, agility and charisma, as well as their capability with various weapons, which increases with each successful use. It also came with a dungeon builder for making custom extensions, which has been used to create hundreds of different Eamon adventures in the decades since.[3]

Despite the fact that they couldn’t come close to capturing the full open-ended gamut of possibility of pen-and-paper D&D, these CRPGs became very popular for one simple reason: a good D&D game required two scarce elements: effort and a good group. The open-ended imaginative landscape of D&D put a tremendous amount of work on the shoulders of the dungeon master, who had to concoct a setting (at the least, a dungeon placed in a wilderness with some nearby town or village at which to rest and restock between excursions), populate it with various challenges and obstacles for the characters in the game to overcome, and then finally simulate it all in real time for hours on end, responding on-the-fly to anything the players might decide to do. Many of the early CRPG authors were dungeon masters who started out by writing digital tools to try to automate away some of this work, then later realized that they could put a complete D&D-like experience on the computer. To get the most out of D&D also required sustaining a campaign of adventures over many sessions, which meant having a consistent group of (typically four or more) willing players who would turn up week after week to keep the game moving forward, and who would not derail the game with incessant jokes, distractions, or arguments. As the manual for one of the early CRPGs, Temple of Apshai, put it:

Ordinary role-playing games require a group of reasonably experienced players, an imaginative and knowledgeable referee/dunjonmaster willing to put in the tremendous amount of time necessary to construct a functioning fantasy world, and large chunks of playing time, since the usual game session lasts four to eight hours (although twenty-hour marathons are not unheard of). DUNJONQUEST solves those problems by offering an already created world with enough detail and variety for dozens of adventures. There is only a single character-your character – pitted against the denizens of the dunjon at any one time, but you can play for just as long or short a period as you like, and return whenever you feel like it. While there are greater practical limits to your actions than is usually the case in a non-computer RPG, there are still a large number of options to choose from.[4]

Whereas adventure games offered an entirely new experience that existed only in digital form, CRPGs (and, as will see, computer wargames), distilled a digital liquor from a pre-existing hobby, boiling off, for better and for worse, all of the costs and uncertainties of dealing with other human players.

Temple of Apshai was by far the most widely available, well-known, and influential CRPG to appear prior to 1981: originally written for the TRS-80, it was later ported to the Commodore PET, and Apple II, and many other later computers (such as the Atari 400/800 and IBM PC). Jim Connelley and Jon Freeman, dungeon master and player, respectively, in a Mountain View, California D&D group, created Apshai in 1979 after first writing a couple of space strategy games—several early software companies got their start in this genre because of the known popularity of Star Trek games. (The first title published by the pseudo-Nordic Brøderbund Software, for example, was Galactic Empire,in 1980.) Connelley and Freeman changed tack at the insistence of their fellow role-players, who had poo-pooed their space games and asked for something more like D&D.[5]

Although, like almost all CRPGs before and since, it was primarily a game about monster-slaying, Apshai pulled in as many role-playing elements as Connelley and Freeman could think of and program in, including the ability to haggle with shopkeepers, parley with monsters, and search for secret doors and traps. The manual contained vivid descriptions of each room in the four levels of Apshai’s dungeon, to make up for the impossibility of storing that much text in the computer’s memory. On level one, room fifteen “is an irregular cave of native rock. The walls and floor are covered with a heavy matting of multi-hued moss. The walls are brilliant reds, greens, and blues, while the floor is a pastel yellow. A wooden box lies topless in the middle of the cavern floor. Inside lies a well-made cloak. The material of the cloak seems to shimmer in the torchlight.”[6]

Two CRPGs that arrived in 1981 were the most important after Apshai in defining the genre; each founded a series of games that lasted into the 1990s.

The first came from Sir-tech Software, although it began as Siro-tech Software, founded by three members of a family that had grown wealthy in construction and manufacturing, Robert, Norman and Fred Sirotek. They got into the microcomputer business software market by staking their capital on the computer skills of a Cornell student named Robert Woodhead, the son of one of the Sirotek’s partners. After producing a database called Info-Tree in 1979, Woodhead pulled his partners reluctantly away from business and into games. Woodhead had an inside lane on good game design, because Cornell had a PLATO system, host to some of the most impressive computer games in existence in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Woodhead’s first game, Galactic Attack, was a simplified Apple II clone of PLATO Empire, a game that combined the galactic warfare framework of the many Star Trek variants with the action gameplay of MIT SpaceWar. Empire put as many as fifty players in competition, each at their own PLATO terminal, but the Apple II buyer would have to content themselves with computer-controlled opposition.[7]

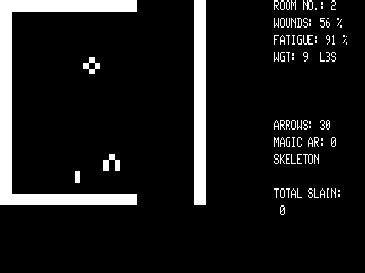

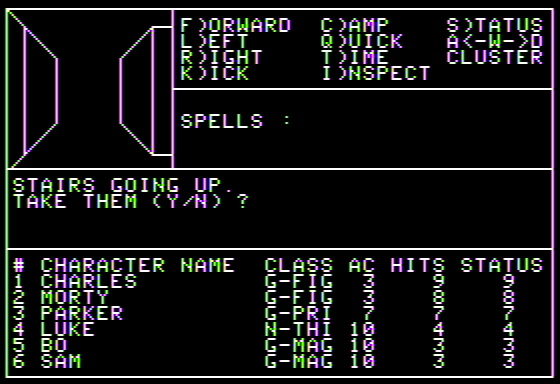

For Siro-tech’s next game, Woodhead tapped Andy Greenberg, a fellow Cornell student, for aid. He had seen a copy of the partially-completed CRPG that Greenberg had written on his own, as a hobby project called Wizardry. For the next year and more, they honed Greenberg’s prototype, finally releasing Wizardry: Proving Grounds of the Mad Overlord in early 1981, under the new imprint of Sir-tech Software. Like Galactic Attack, it borrowed many of its core design elements from a PLATO predecessor, in this case Oubliette. In both games, the player explored dungeons from a first-person, wireframe perspective, with a party of up to six characters of varying classes and races, with a wide variety of potential magic spells at their fingertips. As with Empire, the multiplayer elements were necessarily lost in translation to the personal computer: In Oubliette, individuals could create their own characters and form up into parties to explore the dungeon, but in Wizardry all six characters in the party were puppets of the single player. But Wizardry made considerable improvements in UI (surrounding the first-person dungeon view with various textual information about the party and the available player actions) and in the design of the dungeon (which was now seeded with variety of unique areas to discover and a clear end goal).[8]

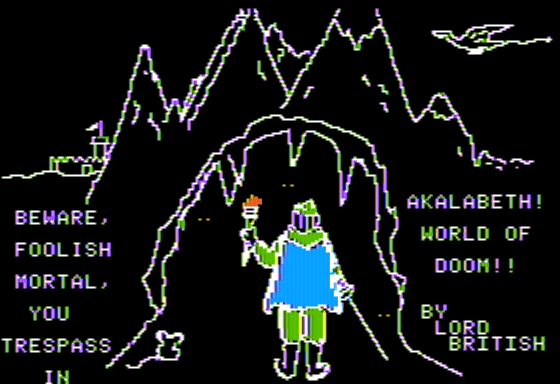

Wizardry proved very successful, but in the long run was eclipsed in sales and fame by the Ultima series, created by Richard Garriott. Garriott grew up in Houston as the son of an astronaut-engineer, and had some early exposure to programming at time-sharing terminals in high school, but he developed a real love for the subject after his parents sent him to a summer computer camp at the University of Oklahoma. He also picked up another passion at camp, Dungeons and Dragons. Back at school the following year, he combined his interests by writing and-rewriting a D&D game in BASIC on the school computer terminal. With financial help from his father, he bought an Apple II Plus system after graduation in the summer of 1979, then matriculated at the University of Texas. There, in addition to picking up yet another nerdy hobby (the Society for Creative Anachronism), he rewrote his game once again to take advantage of the Apple’s high-res graphics. The following summer, his boss at the local ComputerLand store in Houston saw the game and encouraged Garriot to offer it for sale. It sold only a few copies locally, but Garriott began to make real money once a publisher, California Pacific Computer Company, somehow caught wind of the game and picked it up for their catalog.[9]

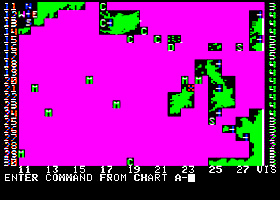

Though Garriott called this first commercial game Akalabeth, we can think of it as Ultima 0. Garriott released Ultima the following year, in 1981, and the two games shared many features in common. Both featured a top-down overland map of a fantasy realm populated with towns and dungeons. When the player enters a dungeon in either game, the perspective changes to a first-person, 3D wireframe view, like that of Wizardry. In Oklahoma, Garriott had picked up the nickname “Lord British” for his urbane accent and vocal mannerisms, which didn’t fit in with the southern drawl of his campmates, and both Akalabeth and Ultima contained a Garriott alter-ego Lord British, who doled out the quests the player needed to complete the game. However, Ultima, with its much more expansive scope and more complex narrative, established the series’ reputation for epic, world-spanning adventures. Alakabeth was designed to be played in a single sitting of dungeon-diving, while Ultima expected you to gather MacGuffins from across four continents, fight a series of space battles, and finally travel back in time to defeat the villain.

Wizardry and its many sequels established a style of game focused on optimizing the abilities and equipment of a group of characters to make an ever-more efficient monster-killing machine. The characters had no independent agency or role in the game; they functioned only as elements of the party. The player was kept at arm’s length, with no individual representing him or her directly in the game. The narrative frame was lightly drawn around this mechanical core. The Ultima series, on the other hand, became more and more focused on story. The games gave the player control of a single character with a specific role in an overarching game narrative, and placed other characters in the world whom you could recruit to join your party, each with their own motivations. The fourth game in the series, Quest of the Avatar, established that the main character in the game is you: a Stranger from our earth summoned across the fourth wall of the computer screen into the magical world of Britannia, fusing the diegetic and non-diegetic elements of the game into one. These two design approaches influenced CRPGs throughout the 1980s and 1990s, with most games drawing heavily from one series or the other.

Even as the CRPG genre took off, other game creators were busy digitizing another part of nerddom. When Joel Billing was seven years old, his father (who had served in the artillery in World War II) introduced him to a game called Tactics II, from publisher Avalon Hill. It pitted two identical modern military forces against each other on a grid overlaying a fictional geographic setting. D&D had sprung from miniature wargaming, which simulated combat scenarios through miniature figures set on a scale model of the battlefield. Through Tactics II, Billings became obsessed with the related but distinct field of board wargaming, which represented forces as cardboard chits and terrain as a hexagonal or square grid printed on paper. This made it much more practical to print and sell complete games, whereas miniature wargames circulated as rules pamphlets, with players supplying their own terrain and figures. In the late 1970s, board wargaming was a vibrant and growing community and market, with membership and annual unit sales both measured in six figures. It was dominated by young men, who typically got into the hobby as teens. The most popular titles covered historical battles or campaigns, especially of the Napoleonic Wars, the U.S. Civil War, and World War II, but board wargaming’s overlap with other parts of nerddom spawned science fiction and fantasy games, as well.[10]

Billings remained fascinated with wargames and military history through his teens and early twenties. In college (at Claremont McKenna College in southern California), he picked up some computer skills, and programmed a simple tank combat game on the school’s PDP-10. Just before graduation in the spring of 1979, he learned about the TRS-80 microcomputer at Radio Shack, and saw potential for applying the power of computers to his favorite hobby. His thinking ran along much the same lines as that of the author of the Temple of Apshai manual, when citing its advantages over pen-and-paper D&D. Given the amount of time and effort involved in learning and playing wargames, an avid gamer could not always find a willing and available gaming partner. But a computer wargame with an automated opponent would be ready to play any time of day or night. Paper wargames also struggled with the problem of “fog of war”: real commanders did not know the exact nature and dispositions of enemy forces, but in a game like Tactics II and its descendants, they were sitting right there on the board, impossible to miss. Some wargames solved this problem with a neutral referee, the only person with a complete view of the state, and who could then adjudicate when pieces were revealed to each player. But the role of referee was ancestral to the D&D dungeon master and had similar problems: finding a dedicated and skilled referee willing to commit the time and effort to a game without getting to actually participate in it was even harder than finding fellow players.[11]

At the time, Billings was working a summer job at Amdahl Corporation in Sunnyvale, California, and he began posting flyers in local hobby shops seeking help from skilled programmers with bringing his concept to life. John Lyon, a thirty-nine-year-old miniatures wargamer with over a decade of programming experience but little career satisfaction, answered his ad. They decided to start with an adaptation of the Avalon Hill boardgame Bismarck, based on the hunt for the eponymous German battleship in the Atlantic by British forces in May 1941. Bismarck did not use a referee, but it could benefit from one – because each player could only search for the enemy Battleship-style, by calling out a grid location where your planes or ships were hunting, there was no way in the game to search for an enemy fleet without revealing the location of your own forces. And the game would be very easy to adapt to the computer by putting the player in charge of the British forces, and leaving the computer with the Germans, who had only a handful of ships and a simple goal of avoiding detection as long as possible. Lyon began plinking away in Joel’s apartment on a text game using a borrowed North Star Horizon computer.[12]

Word of Billings’ plans got to Trip Hawkins, a marketing executive at Apple Computer. Hawkins had also been an avid game player in his youth, having enjoyed Avalon Hill wargames, Dungeons and Dragons, and especially sports simulations like Strat-O-Matic Football and Baseball. He convinced Billings and Lyon to change horses to the Apple II, to take advantage of its full-color graphics, and offered to lend his help with finding them buyers and distribution channels. But Hawkins wouldn’t offer much financial support, nor could Billings get interest from Avalon Hill or existing software publishers, so he abandoned his plans for business school, gathered funding from his family, and formed Strategic Simulations, Inc. (SSI) to publish the game himself. Computer Bismarck, released in early 1980, was a hit, selling over 7,000 copies even at a hefty price tag of $59.95. SSI followed with another copycat wargame (Computer Ambush, based on Avalon Hill’s Sniper), and many more wargames in the years to come, from Napoleon’s Campaigns to the Battle for Normandy. Billings recruited their most wargame prolific designer, Gary Grigsby, when he called the SSI tech support line to ask questions about the submarine game Torpedo Fire, and took the opportunity to pitch Billings on his own in-progress game design. SSI also dipped into the popular space strategy genre with Cosmic Balance, and later branched out into CRPGs as well.[13]

SSI published prolifically, but it was not the only player in the computer wargaming market. Avalon Hill understood the opportunity that digital wargames presented, and began publishing its own line of microcomputer games starting in the summer of 1980 with a batch of five (pretty bad) games. These games were purely text-based, including, ironically, North Atlantic Convoy Raider, a game in which the player takes command of the Bismarck, with orders to destroy British merchant shipping.[14]

Avalon Hill’s 1981 line-up included another text game: Tanktics, a World War II tank battle game by Chris Crawford. Crawford originally wrote the game on an IBM 1130 computer while teaching at a community college in Nebraska in 1976, then self-published a version for the Commodore PET that sold 150 copies. Based on the Avalon Hill board game Panzer Leader, it required the player to track the position of the tanks by moving game pieces on an included board. By the time Avalon Hill edition of Tanktics was published in 1981, Crawford was working at Atari, where he created a much more sophisticated, purely digital and graphical game for his new employer’s line of computers. Eastern Front (1941) gave the player control of the Axis forces during the first year or so of their assault on the Soviet Union, incorporating the effects of weather, terrain, supply lines, and unit morale, and presented it all on a smooth-scrolling map of Eastern Europe. Unlike Tanktics, it was a smash hit, becoming the best-selling title in Atari’s computer software catalog (the Atari Program Exchange).[15]

CRPGs had fairly little effect on the popularity of paper role-playing games, because they were a low-dimensional projection of their source material; they could not replicate the open-ended nature of a refereed game. But a computer wargame could recreate the functionality of a board wargame in full, while eliminating its many inconveniences (in addition to requiring an opponent and complete knowledge of complex rule systems, many wargames required setting up and manipulating hundreds, if not thousands, of cardboard chits). To anyone thinking about the future of wargames, the most impressive feature of Eastern Front was its artificial intelligence. Each Russian unit decides where to move by looking at its immediate surroundings and choosing a location to maximize the strength of the Russian position. The results is an AI that will plug holes in the line, retreat in the face of overwhelming force, and occupy undefended cities. Billings and Lyon had chosen their subject matter to avoid the complexity of coordinating the moves of dozens of computer-controlled units; Crawford tackled it head on and proved that a computer could convincingly simulate a wargame opponent.

This had a devastating effect on the hobby that Billings had so loved. By the mid-1990s, when I was a teen, board wargaming had become almost entirely the province of older men who had picked up the hobby in the 1970s or early 1980s. Young men with an interest in military history (such as I was at the time) played games like SSI’s Panzer General (1994) on their computers instead, driving Avalon Hill, the dominant publisher in the industry, out of business in 1998.[16]

Even more popular, though, than SSI’s wargames, were their sports simulation games: Computer Baseball andComputer Quarterback. Plenty of people in nerddom were also interested in sports, and especially the sports statistics that these games ran on. But more importantly, computers were not just for nerds anymore; by the early 1980s they had spread well beyond the garages and basements of the electronics hobbyists of yore, and could be found in businesses of all sizes, in schoolrooms, and in upper-middle-class households looking to give their children a head start with the technology of the future. These computer owners bought games, too, and richly appointed simulation games helped to set their new prized possessions apart from (much cheaper) game consoles. The popular simulation game of all was Bruce Atwick’s Flight Simulator, later purchased by Microsoft. Thought later games in the series focused on flying real commercial aircraft from real airports, the original Apple II version consisted of a dogfight between pseudo-World War I aircraft over imaginary wireframe terrain. Like Zork, it made a fantastic showpiece for impressing (perhaps skeptical) friends, colleagues, and family members that your very expensive computer was no mere child’s toy.[17]

By 1980, the immersive and detailed experiences provided by adventure games, CRPGs, space strategy games, wargames, and simulation games had, in fact, already defined computer games as a category distinct from the video games produced by Atari and others. These games did not require the special hardware that video game consoles used for moving objects (such as spaceships and missiles) around the screen, but demanded many kilobytes of memory and data storage, and often the ability to save your progress between sessions, all of which the video game consoles lacked. One can already see this boundary being drawn in the periodicals of the day. In this article on game design, for example, in the April 1979 issue of Creative Computing:

What are the elements of a good computer game? It might be best to start with the elements that do not necessarily make a good game. Graphics are important, of course, but remember that it will be very hard to beat the graphics in a commercial video game. Action is very important in any kind of game, but here again, the video game features fast action, and our little home computer may be no match in this department. Surely there must be some element in which the personal computer can out-shine all other mediums. Yes there is, and that element is STRATEGY. No other form of game has the capability for strategic approach that the home computer has because of the computer’s ability to keep track of so many elements that are changing all at once. This probably accounts for the great popularity of the better Star Trek programs around. [18]

This distinction certainly came freighted with more than a little disdain on the part of computer gamers for their less sophisticated cousins: a review of Temple of Apshai praised it as a game “for anyone who is tired of simple ‘video games.’” The first issue of Computer Gaming World, in late 1981, reflected the special relationship between computer gaming and nerddom: it featured a dragon on the cover and dedicated the bulk of its interior to wargames.

The apparent wall of separation, however, between computers and mere video games, belied the fact these simple video games were at the same time completely reshaping the market for the personal computer. That is the subject to which we will turn next.[19]

[1] For a first-person account of the arrival of D&D in 1970s nerddom, see Allen Rausch, “Stephen Colbert on D&D,” GameSpy (August 17, 2004) (http://pc.gamespy.com/pc/dungeons-dragons-online/537989p1.html).

[2] Linda Linwander, “‘D and D’ Plus Sci‐Fi,” New York Times (October 7, 1979).

[3] Apple, Apple II Reference Manual (January 1978), 63-66 (https://apple2history.org/dl/Apple_II_Redbook.pdf). Smith, They Create Worlds, 389-391; Matt Barton and Shane Stacks, Dungeons and Desktops: The History of Computer Role-Playing Games, 2nd edition(Boca Raton: CRC Press, 2019), 70-71; Jimmy Maher, “Eamon, Part 1 ,” Digital Antiquarian (September 18, 2011) (https://www.filfre.net/2011/09/eamon-part-1/), Donald Brown, “The Wonderful World of Eamon,” Recreational Computing (July-August 1980), 33-38.

[4] Epyx Software, Temple of Apshai Instruction Manual (1982), 6 (https://adamarchive.org/archive/Manuals/ADAM%20Software/Temple%20of%20Apshai%20-%20Manual.pdf).

[5] Barton and Stacks, Dungeons and Desktops, 73; Smith, They Create Worlds, 391-393.

[6] Epyx Software, Temple of Apshai Instruction Manual (1982), L1-2.

[7] Jimmy Maher, “The Roots of Sir-Tech,” Digital Antiquarian (March 18, 2013)(https://www.filfre.net/2012/03/the-roots-of-sir-tech/).

[8] Jimmy Maher, “Making Wizardry,” Digital Antiquarian (March 20, 2012)(https://www.filfre.net/2012/03/making-wizardry/); “Game 12: Obuliette,” The CRPG Addict (October 7, 2013) (https://crpgaddict.blogspot.com/2013/10/game-12-oubliette-1977.html); “Game 84: Oubliette,” Data Driven Gamer (August 4, 2019) (https://datadrivengamer.blogspot.com/2019/08/game-84-oubliette.html).

[9] Jimmy Maher, “Lord British,” Digital Antiquarian (December 12, 2011) (https://www.filfre.net/2011/12/lord-british); Jimmy Maher, “Ultima, Part 1,” Digital Antiquarian (February 10, 2012) (https://www.filfre.net/2012/02/ultima-part-1).

[10] Matt Barton, “Matt Chat 181: Joel Billings on Computer Bismarck and More” (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JARauQklGR4); Nicholas Palmer, The Comprehensive Guide to Board Wargaming (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1979) 13, 19; Jon Freeman, The Complete Book of Wargames (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1980), 22.

[11] Jimmy Maher, “Opening the Gold Box, Part 1: Joel Billings and SSI,” Digital Antiquarian (March 4, 2016) (https://www.filfre.net/2016/03/joel-billings-and-ssi); Peterson, Playing at the World, 63-64.

[12] Allan Tommervik, “Exec Strategic Simulations,” Softalk (July 1981), 4-6; Matt Barton, “Matt Chat 181”; Maher, “Opening the Gold Box, Part 1”; Joachim Froholt, “Interview with Joel Billings of SSI and 2by3 Games,” Spillhistorie.no (December 10, 2019) (https://spillhistorie.no/2019/12/10/interview-with-joel-billings-of-ssi-and-2by3-games).

[13] Matt Barton, “Matt Chat 181”; Morgan Ramsay, Gamers at Work: Stories Behind the Games People Play (New York: Springer, 2012), 1-2; “A History of Computer Games,” Computer Gaming World (November 1991), 19; Randy Heuer, “Computer Bismarck,” Creative Computing (August 1980), 31.

[14] “Game #4 : Midway Campaign (1980),” The Wargaming Scribe (May 10, 2021) (https://zeitgame.net/archives/235).

[15] “Chris Crawford,” Computer Gaming World (December 1986), 46; Chris Crawford, “Eastern Front: A Narrative History,” Creative Computing (August 1982), 100-107; Dana Lombardy, “Inside the Industry,” Computer Gaming World (September-October 1982), 2.

[16] Board wargaming did not die out completely. While computers can reproduce all the gameplay features of a wargame, they can’t reproduce the tactile experience of manipulating the pieces, nor the visual presence of a map five feet square or larger. The hobby is supported by small and cautious publishers like GMT and Multi-Man Publishing, who use pre-order systems to gauge interest and issue small print runs (typically a few thousand units) that they are confident they can sell through.

[17] “Game 251: Computer Baseball,” Data Driven Gamer (April 8, 2021) (https://datadrivengamer.blogspot.com/2021/04/game-251-computer-baseball.html); J. Mishcon, “FS1 Flight Simulator,” The Space Gamer (September 1980), 28.

[18] Sol Friedman, “Elements of a Good Computer Game,” Creative Computing (April 1979), 34.

[19] Len Lindsay, “32K Programs Arrive: Fantasy Role Game For The PET,” Compute! (Fall 1979) 86.

Another good survey of the games industry of this era. If anything, it’s too brief. More!

Typos:

* Sentence “find simple character creation in 1978 for the Apple II.” seems out of place.

* Temple of Apshai wasby – Missing space

* finanicial

* sequelsestablished – Missing space

* Panzer General (1994)on – Missing space

Regarding the SCA, you should define it when first mentioned.

LikeLike

Thank you for pointing out those typos! They should be fixed now. That weird sentence must have been a note to self, I have no recollection of writing it, though!

LikeLike