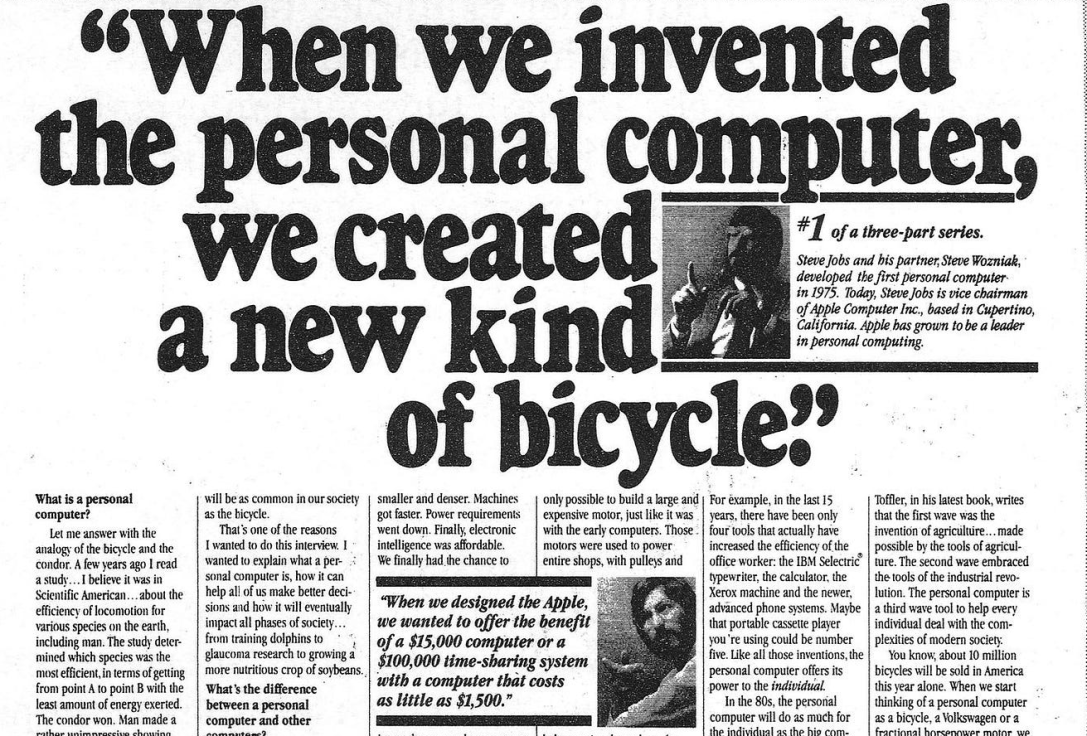

“When man created the bicycle, he created a tool that amplified an inherent ability. That’s why I like to compare the personal computer to a bicycle. …it’s a tool that can amplify a certain part of our inherent intelligence. There’s a special relationship that develops between one person and one computer that ultimately improves productivity on a personal level.”

— Steve Jobs[1]

In December of 1974, hundreds of thousands of copies of the magazine Popular Electronics rolled off the presses and out to newsstands and mailboxes across the United States. The front cover announced the arrival of the “Altair 8800,” and the editorial just inside explained that this new computer kit could be acquired at a price of less than $400, putting a real computer in reach of ordinary people for the first time. The editor declared that “the home computer age is here—finally.”[2] Promotional hyperbole, perhaps, but many of the magazines’ readers agreed that the Altair marked the arrival of a moment prophesied, anticipated, and long-awaited. They devoured the issue and sent in their orders by the thousands.

But Altair was more than just a successful hobby product. That issue of Popular Electronics’ convinced some readers not only to buy a computer, but to form organizations, whether for-profit or non-profit, that would collectively grow and multiply over the coming years into a massive cultural and commercial phenomenon. Some of those readers achieved lasting fame and fortune: In Cambridge, Massachusetts, the Altair cover issue galvanized a pair of ambitious, computer-obsessed friends into starting a business to write programs for the new machine; they called their new venture Micro-Soft. In Palo Alto, California, it stimulated the formation of a new computer club that drew the attention of a local circuit-building whiz named Steve Wozniak. But the announcement of Altair planted other seeds that are now mostly forgotten. In Peterborough, New Hampshire, it inspired the creation of a new magazine aimed at computer hobbyists, called BYTE. In Denver, it inspired a computer kit maker called the Digital Group to start building a rival machine that would be even better.

The arrival of the Altair catalyzed a reaction that precipitated no less than five distinct, but intertwined, social structures. Three were purely commercial: a hardware industry to make personal computers, a software industry to create applications for them, and retail outlets to sell both. The other two mixed commercial and altruistic motivations: a network of clubs and periodicals to share news and ideas within the hobby community, and a cultural movement to promote the higher meaning of the personal computer as a force for individual empowerment. All of these developments seemed, to a casual observer, to appear from nowhere, ex nihilo. But the reagents that fed into this sudden explosion had been forming for years, waiting only for the right trigger to bring them together.

The first reagent was a pre-existing electronics hobby culture. In the 1970s, hundreds of thousands of people, mostly men, enjoyed dabbling in circuit-building and kit-bashing with electronic components. In the United States, they were served by two flagship publications, the aforementioned Popular Electronics and Radio-Electronics. They provided do-it-yourself instructions (an issue of Popular Electronics from 1970, for example, guided readers on how to build a pair of bookcase stereo speakers, a waa-waa pedal, and an aquarium heater), product reviews, classified ads where readers could offer products or services to the community, and more. Retail stores and mail-order services like Radio Shack and Lafayette Radio Electronics provided the hobbyists with the components and tools they needed for their projects, and a fuzzy penumbra of local clubs and newsletters extended out from these larger institutions. This culture provided the medium for the personal computer’s initial, explosive growth.

But why were the hobbyists so excited by the idea of a “home computer” in the first place? That energy came from the second reagent: a new way of communicating with computers which had created a generation of computer enthusiasts. Anyone involved in data processing in the 1950s and 60s would have experienced computers in the form of with batch-processing centers. The user presented a stack of paper cards representing data and instructions to the computer operators, who put the user’s job in a queue for execution. Depending on how busy the system was, they might have to wait hours to collect their results.

But a new mode of interactive computing, created at defense research labs and elite campuses in the late 1950s and early 1960s, had become widely available in colleges, science and engineering firms, and even some high schools by the mid-1970s. When using a computer interactively, a user sitting at a terminal typed inputs on a keyboard and got an immediate response from the computer, either via a kind of automated typewriter called a teletype, or, less commonly, on a visual display. Users got access to this experience in one of two forms: minicomputers were smaller, less expensive machines than the traditional mainframes, low-cost enough that they could be dedicated to small office or department of a larger organization, and sometimes monopolized by one person at a time. Time-sharing systems provided interactivity by splitting a computer’s processing time among multiple simultaneous users, each seated at their own terminal (sometimes connected to a remote computer via the telephone network). The computer could cycle its attention through each terminal quickly enough to give each user the illusion of having the whole computer at their command.[3] The experience of having the machine under your direct command was entirely addictive, at least for a certain type of user, and thousands of hobbyists who had used computers in this way at work or school salivated at the notion of having it on-demand in their own home.

The microprocessor served as the third reagent in the brew from which the personal computer emerged. In the years just prior to the Altair’s debut, the declining price of integrated circuits and a growing demand for cheap computation had led Intel to create a single chip that could perform all the basic arithmetic and logic functions of a computer. Up to that point, if a business wanted to add electronics to their product—a calculator, a piece of automated industrial equipment, a rocket, or what have you—they would design a circuit, assembled from some mix of custom and off-the-shelf chip, that would provide the capabilities needed for that particular application. But by the early 1970s, the cost of adding a transistor to a chip had gotten so low that it made sense in many cases to buy and program a general-purpose computing chip—a microprocessor—that did more than you really needed, but that could be mass-produced to serve the needs of many different customers at low cost. This had the accidental side-effect of bringing the price of a general-purpose computer down to a point affordable to those electronic hobbyists who had been craving the interactive computing experience.

The final reagent was the explosive growth of American middle-class wealth in the decades after the Second World War. The American economy in the 1970s, despite the setbacks of “stagflation,” was an unprecedented engine of wealth and consumption, and Americans acquired new gadgets and gizmos faster than anyone else in the world. In 1973 they purchased 14.6 million cars and 9.3 million color televisions. Though Americans constituted less than six percent of the world’s population, in 1973 they purchased roughly one-third of all cars produced in the world, and one-half of all color televisions (14.6 million and 9.3 million, respectively).[4] When a Big Mac at McDonald’s would run you sixty-five cents and an average new car in the U.S. cost less than $5,000, the first run of Altairs listed at a price of $395, and when kitted out with accessories would easily cost $1,000 or more.[5] The United States was by far the most promising place on earth to find thousands of people willing and able to throw that kind of money at an expensive toy.

For, despite a lot of rhetorical claims about their potential to boost productivity, home computers had almost no practical value in the 1970s. Hobbyists bought their computers in order to play with them: tinkering with the hardware itself to see how it could be expanded, writing software to see what they could make the hardware do, or playing in a more literal sense with computer games, shared for free within the hobby community or, later, purchased in dedicated hobby shops. It took years for the personal computer to evolve into a capable business machine, and years more to become an unquestioned part of everyday middle-class life.

I came along at a later stage of that evolution, part of a second generation of hobbyists who grew up already familiar with home computers. I still remember a clear, warm day when my father pulled up alongside me and my friends on a then-quiet stretch of road as we rode our bicycles back from the candy store a few miles from my house. He rolled down the passenger side window of his Chevy Nova compact and showed me the treasure trove he had just plundered from the electronics store, a plastic satchel containing three computer games sleeved in colorful cardboard: MicroProse’s F-19 Stealth Fighter and Sierra On-Line’s King’s Quest III and King’s Quest IV. Given the balmy weather and the release dates of those titles, it must have been the late summer or early fall of 1988. I was nine years old.

That roadside revelation changed my life. My father helped me install the games onto the Compaq Portable 286 computer that he no longer needed at work, and I became a PC gamer, forcing me to come to grips with the specialized technical knowledge which that entailed in those years: autoexec.bat files, extended and expanded memory, EGA and VGA graphics, IRQ slots, MIDI channels, and more. I learned that we didn’t have to accept the hardware of the computer as a given: it could be opened up, fiddled with, and improved, with additional memory chips and new sound and video cards. To be seriously interested in computer games at that time was, ipso facto, to become a computer hobbyist.

The eager boy is grown, the tech-savvy father is bent with age, the quiet road courses with traffic, and MicroProse and Sierra still exist only as hollowed out brand-names, empty signifiers. Likewise, the personal computer as the Altair generation created it and as my generation found it has also changed out of all recognition. In the first decade of the twenty-first century, the personal computer mutated into three different kinds of device: into an always-on terminal to the Internet (and especially the World Wide Web), into a pocket communicator and attention-thief, and into a warehouse-scale computer.

But even before that, and indeed, even before I discovered the joys and frustrations of Sierra adventure games, the nature of the personal computer was already in flux. The hobbyists of the 1970s cherished a dream of free computing in two senses. First, computing made easily accessible: they believed anyone should be able to get their hands on computing power, cheaply and easily. Second, computing unshackled from organizational control, with hardware and software alike under the total and individual control of the user, who would also be the owner. Steve Jobs famously compared the personal computer to a “bicycle for our minds,” and a bicycle carried these same senses of freedom.[6] It made personal transportation easy, inexpensive, and fun, and it was also a machine that could be modified to the owner’s needs and desires without anyone else’s say so.

For the computer hobbyists of the 1970s, who loved computers for their own sake as much as for what they could actually do, these two forms of freedom went hand in hand. The personal computer rewarded these dedicated apprentices with a feeling of almost mystical power – the ability to cast electronic spells. But in the 1980s, their dreams clashed with the realities of the computer’s evolution into a machine for serious business and then into a consumer appliance. Big businesses wanted control, reliability, and predictability from their capital investments in fleets of computers, not user independence and liberation. Consumers had no patience for the demands of wizardry; they wanted ease-of-use and a guided experience. They felt no sense of loss at having computers whose software or hardware was harder to understand and modify, because they had never intended to do so. The assumption of the hobbyists that personal computer owners would have complete mastery over their machine could not survive these changes. Some embraced these changes as a natural side-effect of the expansion of the audience for the personal computer, others felt them as a betrayal of the personal computer’s entire purpose.

In this series, which I’m calling “A Bicycle for the Mind,” my intention is to follow the arc of these transformations; to trace where the personal computer came from and where it went. It is a story of how a hobby machine became a business machine and a consumer device, and how all three then disappeared into our pockets and our data centers. But it is also a story of how, through it all, the personal computer retained traces of its strange beginnings, as an expensive toy for nerds who believed that computer power could set you free.

[1] Apple Computer Inc,” advertisement in Wall Street Journal, August 13, 1980

[2] Art Salsberg, “The Home Computer Is Here!”, Popular Electronics (January 1975), 4.

[3] In fact, these two forms of interactive computer system overlapped, because in many cases the computer being time-shared was itself a minicomputer.

[4] “G.M. Chief Raises Sales Forecast,” New York Times, April 20, 1976;Peter J. Schuyten, “Color TV Industry Tuning In Record Sales,” New York Times, November 7, 1978.

[5] “McDonalds menu board from 1974. Nice lesson on prices and selection change over time,” Hayward “Blah, Blah, Blah” Blog, May 6, 2014 (https://haywardeconblog.blogspot.com/2014/05/mcdonalds-menu-board-from-1974-nice.html); “1976 New‐Car Price Rose $700 Over 1975,” New York Times, June 7, 1977; Gene Smith, “Color TV Tubes—Expanding Again,” New York Times, October 28, 1973; Department of Energy Vehicle Technologies Office, “Fact #637: August 23, 2010 World Motor Vehicle Production” (https://www.energy.gov/eere/vehicles/fact-637-august-23-2010-world-motor-vehicle-production).

[6] Advertisement for Apple Computer Inc, Wall Street Journal, August 13, 1980.

Glad to see your new series is up!

I have greatly enjoyed all of your writings and glad that I now have them safely tucked away in ye old Kindle library too.

LikeLike

There should have been room for both kinds of computing. There should still be room for both. Sure enough, just the other day a (younger, I think) friend was writing about the experience of installing Arch Linux manually, and what it can teach you as opposed to using a friendly, guided wizard. Those who want out-of-the-box comfort can still have it without ruining computers for the rest of us. Nope, that attitude was promoted, by the likes of – that’s right – Steve Jobs, who correctly surmised that they can sell more to passive, uninformed customers. And now it’s a mess.

LikeLike