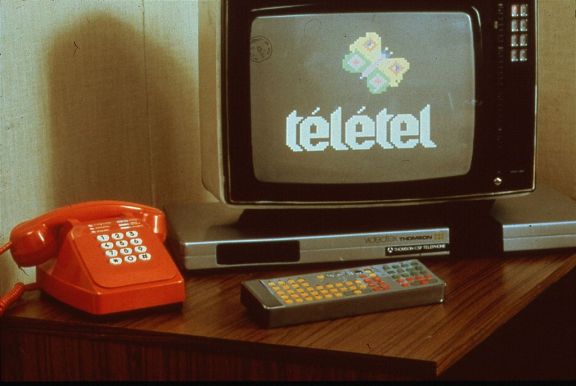

In the spring of 1981, after several smaller trials, The French telecommunications administration (Direction générale des Télécommunications, or DGT), began a large-scale videotex experiment in a region of Brittany called Ille-et-Vilaine, named after its two main rivers. This was the prelude to the full launch of the system across l’Hexagone in the following year. The DGT called their new system Télétel, but before long everyone was calling it Minitel, a synecdoche that derived from the name of the lovable little terminals that were distributed free of charge, by the hundreds of thousands, to French telephone subscribers.

Among all the consumer-facing information service systems in this “era of fragmentation” Minitel deserves our special attention, and thus its own chapter in this series, for three particular reasons. First, the motive for its creation. Other post, telephone, and telegraph authorities (PTTs) built videotex systems, but no other state invested as heavily in making it a success, nor gave so much strategic weight to that success. Entangled with hopes for a French economic and strategic renaissance, Minitel was meant not just to produce new telecom revenues or generate more network traffic, but to prime the pump for the entire French technology sector.

Second, the extent of its reach. The DGT provided Minitel terminals to subscribers free of charge, and levied all charges at time of use rather than requiring an up-front subscription. This meant that, although many of them used the system infrequently, more people had access to Minitel than to even the largest American on-line services of the 1980s, despite France’s much smaller population. The comparison to its nearest direct equivalent, Britain’s Prestel, which never broke 100,000 subscribers, is even more stark.

Finally, there is the architecture of its backend systems. Every other commercial purveyor of digital services was a monolith, with all services hosted on their own machines. While they may have collectively formed a competitive market, each of their systems were structured internally as a command economy. Minitel, despite being the product of a state monopoly, was ironically the only system of the 1980s that created a free market for information services. The DGT, acting as an information broker rather than information supplier, provided one possible model for exiting the era of fragmentation.

Playing Catch Up

It was not by happenstance that the Minitel experiments began in Brittany. In the decades after World War II, the French government had deliberately seeded the region, whose economy still relied heavily upon agriculture and fishing, with an electronics and telecommunications industry. This included two major telecom research labs: the Centre Commun d’Études de Télévision et Télécommunications (CCETT) in Rennes, the region’s capital, and a branch of the Centre National d’Études des Télécommunications (CNET) in Lannion, on the northern coast.

Themselves a product of an effort to bring a lagging region into the modern era, by the late 1960s and early 1970s these research departments found themselves playing catch up with their peers in other countries. The French phone network of the late 1960s was an embarrassment for a country that, under de Gaulle, wished to see itself as a resurgent world power. It still relied heavily on switching infrastructure built in the first decades of the century, and only 75% of the network was automated by 1967. The rest still depended on manual operators, which had been all but eliminated in the U.S. the rest of Western Europe. There were only thirteen phones for every 100 inhabitants of France, compared to twenty-one in neighboring Britain, and nearly fifty in the countries with the most advanced telecommunications systems, Sweden and the U.S.

France therefore began a massive investment program of rattrapage, or “catch up,” in the 1970s. Rattrapage ramped up steeply after the 1974 election of Valéry Giscard d’Estaing to the presidency of France, and his appointment of a new director for the DGT, Gérard Théry. Both were graduates of France’s top engineering school, l’École Polytechnique, and both believed in the power of technology to improve society. Théry set about making the DGT’s bureaucracy more flexible and responsive and Giscard secured 100 billion francs in funding from Parliament for modernizing the telephone network, money that paid for the installation of millions more phones and the replacement of old hardware with computerized digital switches. Thus France dispelled its reputation as a sad laggard in telephony.

But in the meantime new technologies had appeared in other nations that took telecommunications in new directions – videophone, fax, and the fusion of computer services with communication networks. The DGT wanted to ride the crest of this new wave, rather than having to play catch up again. In the early 1970s, Britain announced two separate teletex systems, which would deliver rotating screens of data to television sets in the blanking intervals in television broadcasts. CCETT, DGT’s joint venture with France’s television broadcaster, the Office de radiodiffusion-télévision française (ORTF) launched two projects in response. DIDON1 was modeled closely on the the British television broadcasting model, but ANTIOPE2 took a more ambitious tack, to investigate the delivery of screens of text independently of the communications channel.

Bernard Marti headed the ANTIOPE team in Rennes. He was yet another polytechnichien (class of 1963), and had joined CCETT from ORDF, where he specialized in computer animation and digital television. In 1977, Marti’s team merged the ANTIOPE display technology with ideas borrowed from CNET’s TIC-TAC3, a system for delivering interactive digital services over telephone. This fusion, dubbed TITAN4, was basically equivalent to the British Viewdata system that later evolved into Prestel. Like ANTIOPE it used a television to display screens of digital information, but it allowed users to interact with the computer rather than merely receiving data passively. Moreover, both the commands to the computer and the screen data it returned passed over a telephone line, not over the air. Unlike Viewdata, TITAN supported a full alphabetic keyboard, not just a telephone keypad. In order to demonstrate the system at a Berlin trade fair, the team used France’s Transpac packet-switching network to mediate between the terminals and the CCETT computer in Rennes.

Théry’s lab had assembled an impressive tech demo, but as of yet none of it had left the lab, and it had no obvious path to public use.

Télématique

In the fall of 1977, DGT director Gerard Théry, satisfied with how the modernization of the phone network was progressing, turned his attention to the British challenge in videotex. To develop a strategic response, he first looked to CCETT and CNET, where he found TITAN and TIC-TAC prototypes ready to be put to use. He turned these experimental raw materials over to his development office (the DAII) to be molded into products with a clear path to market and business strategy.

The DAIIn recommended pursuing two projects: first, a videotex experiment to test out a variety of services in a town near Versailles, and second, investment in an electronic phone directory, intended to replace the paper phone book. Both would use Transpac as the networking backbone, and TITAN technology for the frontend, with color imagery, character-based graphics, and a full keyboard for input.

The strategy the DAII devised for videotex differed from Britain’s in three important ways. First, whereas Prestel hosted all of the videotex content themselves, the DGT planned to serve only as a switchboard from which users could reach any number of different privately-hosted service providers, running any type of computer that could connect to Transpac and serve valid ANTIOPE data. Second, they decided to abandon the television as the display unit and go with custom, all-in-one terminals. People bought TVs to watch TV, the DGT leadership reasoned, and would not want to tie up their screen with new services like the electronic phone book. Moreover, cutting the TV set out of the picture meant that the DGT would not have to negotiate over the launch with their counterparts at Télédiffusion de France (TDF), the successor to the ORDF5. Finally, and most audaciously, France cracked the chicken-and-egg problem (that a network without users was unattractive to service providers and vice versa) by planning to lease those all-in-one videotex terminals free of charge.

Despite these bold plans, however, videotex remained a second-tier priority for Théry. When it came to ensuring DGT’s place at the forefront of communications technology, his focus was on developing the fax into a nationwide consumer service. He believed that fax messaging could take over a huge portion of the market for written communication from the post office, whose bureaucrats the DGT looked upon as hidebound fuddy-duddies. Théry’s priorities changed within months, however, with the completion of a government report in early 1978 entitled The Computerization of Society. Released to bookstores in a paperback edition in May, it sold 13,500 copies in its first month, and a total of 125,000 copies over the following decade, quite a blockbuster for a government report6 How did such a seemingly recondite topic engender such excitement?

The authors, Simon Nora and Alain Minc, officers in the General Inspectorate of Finance, had been asked to write the report by the Giscard government in order to consider the threat and the opportunity presented by the growing economic and cultural significance of the computer. By the mid-1970s, it was becoming clear to most technically-minded intellectuals that computing power could and likely would be democratized, brought to the masses in the form of new computer-mediated services. Yet for decades, the United States had led the way in all forms of digital technology, and American firms held a seemingly unassailable grip on the market for computer hardware. The leaders of France considered the democratization of computers a huge opportunity for French society, yet they did not want to see France become a dependent satellite of a dominating foreign power.

Nora and Minc’s reported presented a synthesis that resolved this tension, proposing a project that would catapult France into the post-modern age of information. The nation would go directly from trailing the pack in computing to leading it, by building the first national infrastructure for digital services – computing centers, databases, standardized networks – all of which would serve as the substrate for an open, democratic marketplace in digital services. This would, in turn, stimulate native French expertise and industrial capacity in computer hardware, software, and networking.

Nora and Minc called this confluence of computers and communications télématique, a fusion of telecommunications and informatique (the french word for computing or computer science). “Until recently,” they wrote,

computing… remained the privilege of the large and the powerful. It is mass computing that will come to the fore from now on, irrigating society, as electricity did. La télématique, however, in contrast to electricity, will not transmit an inert current, but information, that is to say, power.

The Nora-Minc report, and the resonance it had within the Giscard government, put the effort to commercialize TITAN in a whole new light. Before the report, the DGT’s videotex strategy had been a response to their British rivals, intended to avoid being caught unprepared and forced to operate under a British technical standard for videotex. Had it remained only that, France’s videotex efforts might well have languished, ending up much like Prestel, a niche service for a few curious early adopters and a handful of business sectors that it found it useful.

After Nora-Minc, however, videotex could only be construed as a central component of télématique, the basis for building a new future for the whole French nation, and it would receive more attention and investment than it might otherwise ever have hoped for. The effort to launch Minitel on a grand scale gained backing from the French state that might otherwise have failed to materialize, as it did for Théry’s plans for a national fax service, which dwindled to a mere Minitel printer accessory.

This support included the funding to provide millions of terminals to the populace, free of charge. The DGT argued that the cost of the terminals would be offset by the savings from no longer printing and distributing the phone book, and from new network traffic stimulated by the Minitel service. Whether they sincerely believed this or not, it provided at least a fig leaf of commercial rationale for a massive industrial stimulus program, starting with Alcatel (paid billions of francs to manufacture terminals) and running downstream to the Transpac network, Minitel service providers, the computers purchased by those providers, and the software services required to run an on-line business.

Man in the Middle

In purely commercial terms, Minitel did not in fact contribute much to the DGT’s bottom line. It first achieved profitability on an annual basis in 1989, and if it ever achieved overall net profitability, it was not until well into its slow but terminal decline in the later 1990s. Nor did it achieve Nora and Minc’s aspiration to create an information-driven renaissance of French industry and society. Alcatel and other makers of telecom equipment did benefit from the contracts to build terminals, and the French Transpac network benefited from a large increase in traffic – though, unfortunately, with the X.25 protocol they turned out to have bet on the wrong packet-switching technology in the long-term. The thousands of Minitel service providers, however, mostly got their hardware and systems software from American providers. The techies who set up their own online services eschewed both the French national champion, Bull, and the dreaded giant of enterprise sales, IBM, in favor scrappy Unix boxes from the likes of Texas Instruments and Hewlett-Packard.

So much for Minitel as industrial policy, what about its role in enervating French society with new information services, which would reach democratically into both the most elite arrondissements of Paris and the plus petit village of Picardy? Here it achieved rather more, though still mixed, success. The Minitel system grew rapidly, from about 120,000 terminals at its initial large-scale deployment in 1983, to over 3 million in 1987 and 5.6 million in 1990.7 However, with the exception of the first few minutes of the electronic phonebook, actually using those terminals cost money on a minute-by-minute basis, and there’s no doubt that usage was distributed much more unequally than the equipment. The most heavily used services, the online chat rooms, could easily burn hours of call time in an evening, at a base rate of 60 francs per hour (equivalent to about $8, more than double the U.S. minimum wage at the time).

Nonetheless, nearly 30 percent of French citizens had access to a Minitel terminal at home or work in 1990. France was undoubtedly the most online country (if I may use that awkward adjective) in the world at that time. In that same year, the largest two online services in the United States, that colossus of computer technology, totaled just over a million subscribers, in a population of 250 million8. And the catalog of services that one could dial into grew as rapidly as the number of terminals – from 142 in 1983 to 7,000 in 1987 and nearly 15,000 in 1990. Ironically, a paper directory was needed to index all of the services available on this terminal that was intended to supplant the phone book. By the late 1980s that directory, Listel, ran to 650 pages.9

Beyond the DGT-provided phone directory, services ran the gamut from commercial to social, and covered many of the major categories we still associate today with being online – shopping and banking, travel booking, chat rooms, message boards, games. To connect to a service, a Minitel user would dial an access number, most often 3615, which connected his phone line to a special computer in his local telephone switching office called a point d’accès vidéotexte, or PAVI. Once connected to the PAVI, the user could then enter a further code to indicate which Minitel service they wished to connect to. Companies plastered their access code in a mnemonic alphabetic form onto posters and billboards, much as they would do with website URLs in later decades: 3615 TMK, 3615 SM, 3615 ULLA.

The 3615 code connected users into the PAVI’s “kiosk” billing system, introduced in 1984, which allowed Minitel to operate much like a news kiosk, offering a variety of wares for sale from different vendors, all from a single convenient location. Of the sixty francs charged per hour for basic kiosk services, 40 went to the service itself, and twenty to the DGT to pay for the use of the PAVI and the Transpac network. All of this was entirely transparent to the user; the charges would appear automatically on their next telephone bill, and they never needed to provide payment information to establish a financial relationship with the service provider.

As access to the open internet began to spread in the 1990s, it became popular for the cognoscenti to retrospectively deprecate the online services of the era of fragmentation – the CompuServes, the AOLs – as “walled gardens”10. The implied contrast in the metaphor is to the freedom of the open wilderness. If CompuServe is a carefully cultivated plot of land, the internet, from this point of view, is Nature itself. Of course the internet is no more natural than CompuServe, nor Minitel. There is more than one way to architect an online service, and all of them are based on human choices. But if we stick to this metaphor of the natural versus the cultivated, Minitel sits somewhere in between. We might compare it to a national park. Its boundaries are controlled, regulated, and tolled, but within them one can wander freely and visit whichever wonders might strike your interest.

DGT’s position in the middle of the market between user and service, with a monopoly on the user’s entry point and the entire communications pathway between the two parties, offered advantages over both the monolithic, all-inclusive service providers like CompuServe and the more open architecture of the later Internet. Unlike the former, once past the initial choke point, the system opened out into a free market of services unlike anything else available at the time. Unlike the latter, there was no monetization problem. The user paid automatically for computer time used, avoiding the need for the bloated and intrusive edifice of ad-tech that supports the bulk of the modern Internet. Minitel also offered a secure end-to-end connection. Every bit traveled only over DGT hardware, so as long as you trusted both the DGT and the service to which you were connected, your communications were safe from attackers.

This system also had some obvious disadvantages compared to the Internet that succeeded it, however. For all is relative openness, one could not just turn on a server, connect it to the net, and be open for business. It required government pre-approval to make your server accessible via a PAVI. More fatally, the Minitel’s technical structure was terribly rigid, tied to a videotex protocol that, while advanced for the mid-1980s, appeared dated and extremely restrictive within a decade.11 It supported pages of text, in twenty-four rows of forty characters each (with primitive character-based graphics) and nothing more. None of the characteristic features of the mid-1990s World wide Web – free-scrolling text, GIFs and JPEGs, streaming audio, etc. – were possible on Minitel.

Minitel offered a potential road out of the era of fragmentation, but, outside of France, it was a road not taken. The DGT, privatized as France Télécom in 1988, made a number of efforts to export the Minitel technology, to Belgium, Ireland, and even the U.S. (via a system in San Francisco called 101 Online). But without the state-funded stimulus of free terminals, none of them had anything like the success of the original. And, with France Télécom, and most other PTTs around the world, now expected to fend for themselves as lean businesses in a competitive international market, the era when such a stimulus was politically viable had passed.

Though the Minitel system did not finally cease operation until 2012, usage went into decline from the mid-1990s onward. In its twilight years it still remained relatively popular for banking and financial services, due to the security of the network and the availability of terminals with an accessory that could securely read and transmit data from banking and credit cards. Otherwise, french online enthusiasts increasingly turned to the Internet. But before we return to that system’s story, we have one last stop to visit on our tour of the era of fragmentation.

Further Reading

Julien Mailland and Kevin Driscoll, Minitel: Welcome to the Internet (2017)

Marie Marchand, The Minitel Saga (1988)

- Diffusion de données sur un réseau de télévision, or broadcasting of data on a television network. ↩

-

Acquisition numérique et télévisualisation d’images organisées en pages

d’ecriture, or digital acquisition and display of pictures organized into pages of text. ↩ - terminal intégré comportant téléviseur et appel au clavier, or integrated television terminal with keyboard control. ↩

- Terminal interactif de télétexte à appel par numérotation, or interactive dial-up teletex terminal. ↩

- Indeed, dealing with British TV manufacturers proved a major hindrance to the successful launch of Prestel. ↩

- Andrée Walliser, “Le rapport ‘Nora-Minc’: Histoire d’un best-seller” (1989). ↩

- Statistics from Mailland and Driscoll, Minitel, 13. ↩

- Eben Shapiro, “New Features Are Planned By Prodigy,” The New York Times, September 6, 1990. ↩

- Mailland and Driscoll, Minitel, 23. ↩

- https://books.google.com/ngrams/graph?content=%22+walled+garden+%22&year_start=1960&year_end=2008&corpus=15&smoothing=3 ↩

- The degree of rigidity of Minitel depends on what you mean by Minitel. The terminal itself (Minitel strictly speaking) could connect to arbitrary computers over the regular telephone network. But its unlikely that many users ever employed this mode, and to do so was essentially no different from using a home computer and modem to dial up service like The Source or CompuServe. It had nothing to do with Minitel in the larger sense as a unified system (officially known as Télétel), and surrendered all of the advantages of the kiosk and the Transpac packet-switching network. ↩

There were a few more benefits from the teletex push in France, although they are hard to quantify. For starters, French TVs had to be equipped with a 21-pin Euro-SCART input (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SCART), known as Peritel in France (for Television Peripheral). The big Peritel connector offered an RGB and sound input. Its robust design made it much harder to destroy than, say, a VGA connector, as it was almost impossible to bend the pins.

The availability of the Peritel input on French TV sets made it very easy to connect home computers and get a good image quality, superior to the video quality obtainable from an antenna cable. Early French home computer users benefited greatly from this connector, which alleviated the need for a dedicated color monitor – one could get a used TV instead of purchasing an expensive monitor.

A drawback of Minitel was that French companies were initially very reluctant to embrace Internet e-commerce. The Minitel worked perfectly well to get online orders from their customers, provided the customers didn’t insist on a picture. Also, many companies used the 3615 channel for their online ordering service, which meant customers also paid a few dollars to place a typical order. The Minitel e-commerce servers made money even without sales! The companies’ Q&A forums and service departments also ensured consumers made an increased use of the 3615 numbers for after-sale questions, thus generating more income, The IT department were respectable money makers back then!

In comparison, the Internet sites were enormous upfront investments that turned IT departments into cost centers, effectively depriving them of their ability to self-support. IT managers were understandably unhappy about the transition.

LikeLike

Thanks for the informative comment!

LikeLike